Move over, Katniss Everdeen. For archerfish, the odds are ever in their favor, according to new research from Wake Forest University.

The sharp-shooting fish’s ability to spit water to hit food targets has been well documented, but a new study published online in the journal Zoology showed for the first time that there is little difference in the amount of force delivered by their water jets to targets at different distances. And, when given the choice, the fish preferred closer targets.

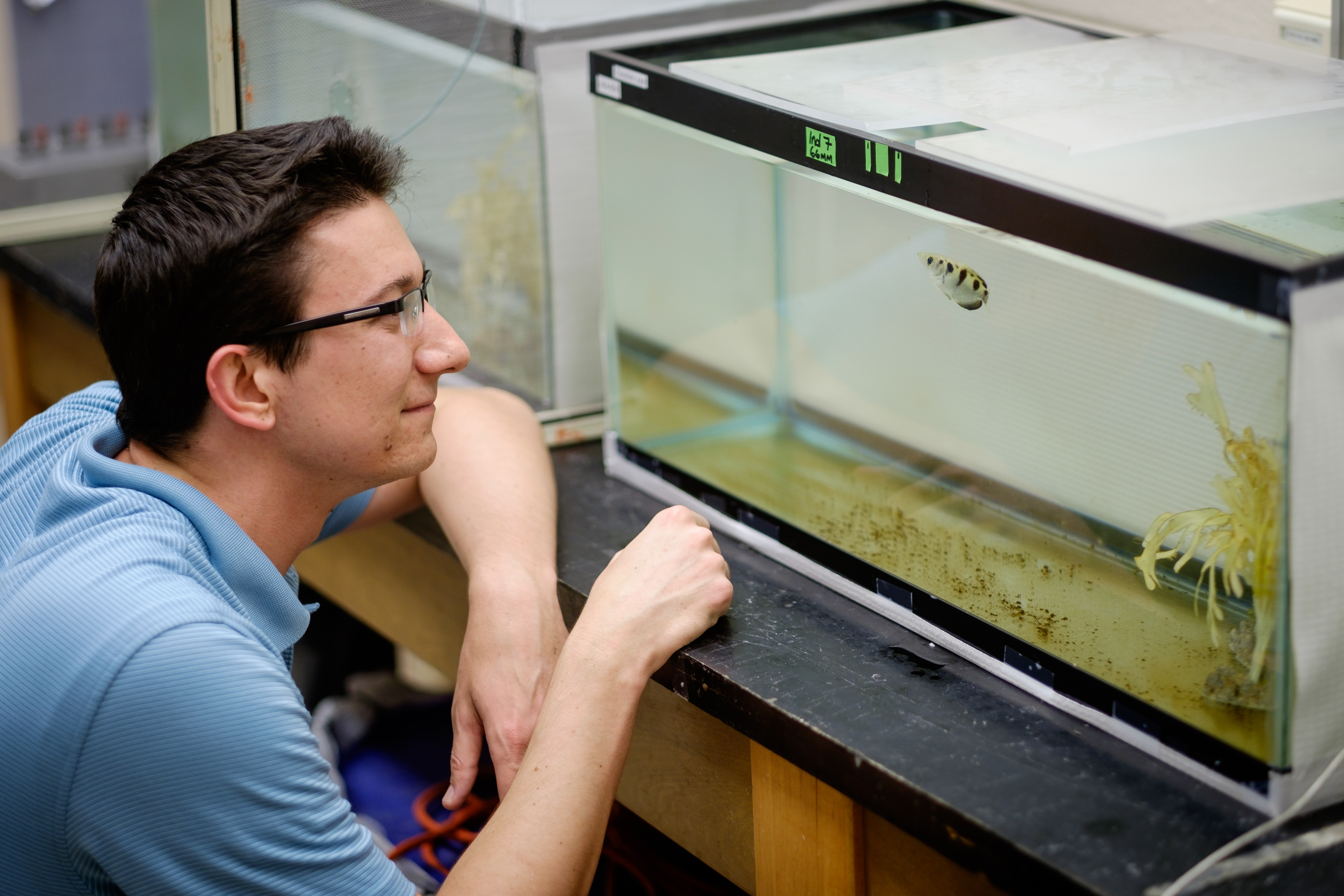

The study was co-authored by Wake Forest researchers Morgan Burnette, a biology graduate student, and Miriam Ashley-Ross, associate professor of biology, whose work focuses on the mechanics of animal behavior in a variety of animal species.

“The force of their jets of water isn’t decreasing by much when they shoot at a distant target,” Burnette said, “but the fish consistently chose closer targets to ensure a food payoff because, ultimately, it’s about whether the fish is going to eat or not that day.”

Described as nature’s sharpshooters or water pistols, archerfish inhabit the mangroves of southeast Asia and northern Australia. When the fish spot small insects on overhead branches and leaves, they spit a stream of water from their mouths that can dislodge that insect, causing it to fall onto the water’s surface. Due to the complex structure of the vegetation in their environment, the distance a shot would have to travel to a potential target may vary considerably. A shooter also must compete with other archerfish for the fallen prey.

The first step toward this goal was to understand how, or even if, the forces from the water jet were different, depending on how far away the fish’s target was. Last year, another research group demonstrated that the fish could alter how the stream travels to and hits a target, based on the distance to that target. The fish shoots a water stream that merges together into a single, globular mass just prior to impact; the fish can determine how far its target is and can adjust accordingly when jet merging occurs. This finding implied that forces to distant targets could be similar to forces delivered to closer targets, and Burnette and Ashley-Ross set out to test this idea.

From the archerfish in their lab, they measured the force at impact and also used high-speed video cameras to capture the impact of the water jet at 500 frames per second.

What Burnette found was that even when the target is relatively far away from the fish (up to six times the body length of the animal), the forces on the target showed little reduction with respect to a closer target. What contributed to this consistency? The high-speed videos revealed that the fish were also capable of producing jets of water that merged into a single mass just before impact, even to the furthest target. In another part of the study, they gave the fish a choice: shoot down a close target or a more distant target, and see which one the fish would choose first.

“It was really interesting that the fish would consistently choose targets that were closer even though we had shown that the forces didn’t change very much with distance,” Burnette said. “Choosing a closer target, then, reduces the amount of time that a bystander has to respond to get the dislodged insect.”

Ashley-Ross said that to simply characterize the archer fish as nature’s squirt gun isn’t quite accurate, because the fish behavior is a lot more complicated than that. Previous studies have compared the calculations the fish are making to what a baseball outfielder is doing, she said, which is figuring out where the ball is going to drop and where they need to be to intercept.

“It’s the same exact type of spatial calculation,” she said. “This study gives us one more window into the complexity of animal experience. Our bias is to think that fish are just dumb and don’t have a whole lot going on and that’s not true. The fish are making very sophisticated calculations.”

Further work on this project is being conducted by Hannah Dabagian, a senior biology major; undergraduate research assistants who were involved, but have since graduated, included Paul Morris, Andrew Harvey and Hampton Sasser.

Categories: Faculty, Research, Student, Top Stories, Uncategorized

Headlines

Wake Forest in the News

Wake Forest regularly appears in media outlets around the world.