Mighty Mealworms: Solution for food insecurity and pollution

Biology students at Wake Forest University are using mealworms to solve two global problems – food sustainability and plastic pollution.

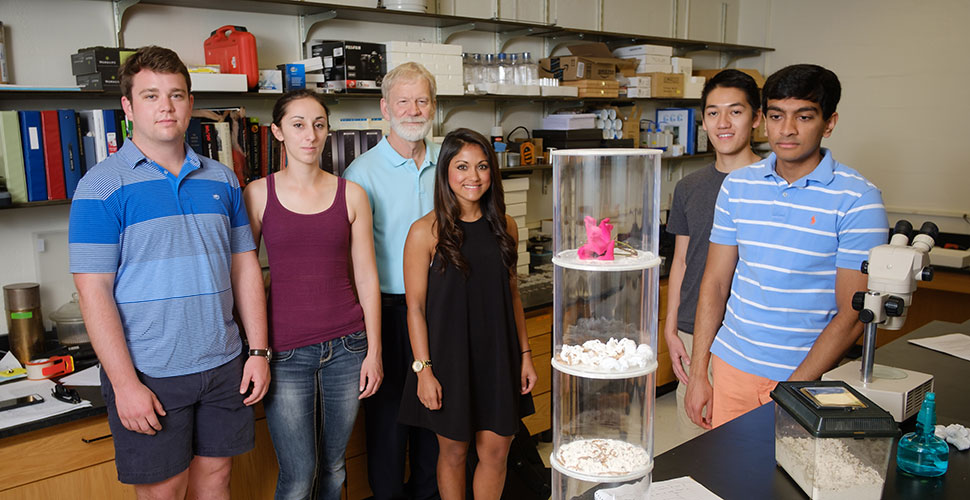

Four graduating seniors and a junior, all biology majors, were chosen to team up on a project for the Global Biomimicry Design Challenge, an annual competition that addresses critical sustainability issues using nature as a guide. The team is made up of seniors Sumi Mahajan, Pascal Dangtran, Andrew Barth, Chirag Patel and junior Meagan Rosenberg. Biology professor Bill Conner, the Lelia and David Farr Professor of Innovation, Creativity and Entrepreneurship (ICE), is their advisor.

Connor said the students were excited to learn that mealworms eat Styrofoam, and other forms of polystyrene foam, a finding published last year by a Stanford University research team.

“That’s pretty exciting science and the students grabbed onto that concept and developed their idea.” Bill Conner, professor of biology

Using the Stanford Styrofoam findings as a springboard, the team designed a vertical mealworm garden to raise mealworms for three sustainable uses: to breakdown plastic, provide food for humans, and use waste as fertilizer.

Mahajan said the team started doing research on mealworms, which are the worm-like larvae of darkling beetles. “We found they are high in protein and already a food source, so we decided to combine their plastic-eating capability with a vertical garden to come up with a contained, sustainable project that would be affordable and easy to duplicate,” she said.

Mealworms are “found globally and can be easily used as a sustainable resource,” said Rosenberg, adding that a vertical mealworm garden doesn’t take up much space and can be made out of a variety of materials.

Patel said their project could be an affordable resource in third-world countries for several options. “People can use the collected frass (insect excrement) as a fertilizer and consume the mealworms as part of their diets. This project has real-world applications and has taught us to learn how to be creative in problem solving.”

Titled “Styrofoam to Food,” the vertical garden has four parts that follow the insect through its brief life cycle. The students used clear plexiglass containers stacked on top of each other. Adult beetles inhabit the top section and mate. Their eggs fall into the second section, hatching into larvae to eat the Styrofoam. The team tried several types before finding that the mealworms prefer packing peanuts.

The mealworms then go into the third section where they mature and eat flour which helps to clean their palates, or guts. As they mature in the third section, their frass falls to the bottom section and can be collected for fertilizer. At this stage, they are either used as a food source or allowed to develop into the pupae stage and become beetles, completing the life cycle.

Dangtran said working on the project has been interesting because of team members’ differences overall and in their areas of study – chemistry, finance, entrepreneurship. “As a team we have such different backgrounds and we’ve been pulling knowledge together to come up with creative solutions.”

Barth said it’s been “cool” to work on a project that could “address food insecurity and help the environment at the same time.”