Disturbing the Peace: Wake Forest and the Arts

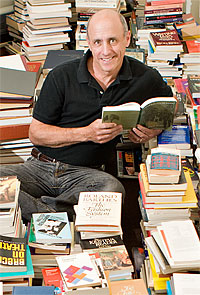

David Lubin

Convocation Address

In one of the last speeches he gave before he was assassinated, President John F. Kennedy spoke eloquently about the importance of the arts in democracy. The worth of a country, he observed, is inseparable from the quality of its arts, and no nation can be deemed great that does not produce and admire great art. “I look forward,” he concluded, “to an America which commands respect throughout the world not only for its strength but for its civilization as well.”

The Kennedy administration is renowned for its avid support of the arts, but it was the post-Kennedy sixties that proved a heyday of artistic culture in America. The arts flourished in those years as never before. Part of the reason for this is legislation signed in 1965 by Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, creating the National Endowment for the Arts, commonly known as the NEA, which began bountifully dispensing much-needed funds not only to individual creative artists — painters, composers, dancers, poets — but also to regional theaters, museums, symphony orchestras, and other non-profit organizations that provided communities across the land with a forum for artistic creativity. It’s worth noting, by the way, that this university’s various programs in the arts took shape during this period of heightened public interest.

David Lubin

Yet it wasn’t simply the abundance of public funding that did so much to bolster the arts. The times themselves, as Dylan would say, were a-changing and in a way that was remarkably energizing. Shaken out of the lethargy of the fifties by the Civil Rights movement, feminism, environmentalism, gay liberation, and a slew of other disturbances in the status quo, artists, patrons, and even ordinary citizens, many of whom previously regarded the arts as mere window dressing, now took them seriously as an engine of social change. Arguments about the meaning and social utility of the arts raged, with those on the right saying one thing and those on the left another. The vociferousness of these debates, their tumultuous nature, proved artistically productive. They fertilized the cultural soil.

Today, in the present climate of ideological divisiveness, with cant from one side at odds with dogma from another, we may have lost our capacity for serious debate about art and its meanings. There’s much less room these days for political fluidity. We’re stuck in a binary system. You’re either a conservative or a liberal (or a variation thereof), and once you’ve decided what side you’re on, you’re virtually locked in place, your taste in art, like that in clothes, sports teams, and political pundits, so rigidly predetermined that there’s almost no escape. Culturally, we live in gated communities, surrounding ourselves with friends who look and talk just like us, and we’re either too complacent or afraid to venture outside the gate — complacent, because we like best what we already know; afraid, because we don’t want to expose ourselves to ideas and emotions and points of view that might disturb our anxiously guarded equilibrium.

This is to say, we’ve become exceptionally close-minded. We think in lockstep. I don’t care if you regularly watch CNN or Fox News, Keith Olbermann or Bill O’Reilly, Pat Robertson or Jon Stewart; if you prefer the Huffington Post or the Drudge Report; you’re addicted, like most everyone else, to preformed ideas and predigested feelings. This is the nature of contemporary pop culture in America, including political pop culture. It makes life simple; it eliminates choice. You don’t need to think for yourself, even though the pandering media and political gurus and express-your-individuality-through-consumption advertisers do their best to flatter you into believing that you, unlike the poor sods on the other side, actually make up your own mind. The sobering fact of the matter is that we usually don’t make up our own minds, we leave it to church leaders or campaign strategists or op-ed writers or talk-radio hosts or marketing experts to do that for us.

In the age of modern mass communications, with our preferred media outlets all-but hot-wired into our brains and our minds under perpetual colonization by thought-merchants and other purveyors of pre-packaged ideas, there seems to be little chance of reversing this trend. One of our last, best hopes for that is represented by the arts. That’s because they pose profound questions about morality, society, human existence, and so forth without providing answers. That’s when you know you’re in the presence of art and not a cheap imitation-when it pushes you outside of your shell or at the very least knocks a crack in that shell; when it stirs you with feelings that are new to you, strange, unfamiliar, perhaps wonderful, perhaps disturbing; when it violates your habitual ways of thinking; when it reassembles your internal architecture; when it makes you glimpse, even if only momentarily, how the world looks and feels to people who are much richer or poorer than you, blacker or whiter, stronger or weaker, happier or sadder.

I’d like to share with you a personal anecdote on this theme. A couple weeks after 9/11, my insides, like everyone else’s, were still raw and hurting. I needed to find some way of making sense of what had happened, some comprehension of why the hijackers had done such a terrible thing. This was certainly not because I wanted to excuse them or condone their behavior or, as some commentators absurdly claimed, because liberals hate their country and prefer to side with its enemies. But I do believe that the best defense against one’s enemies is to get some purchase on their point of view and see how things look through their eyes. We call it military intelligence when an organization gathers secret information about the enemy’s strategic moves. Isn’t it military stupidity to ignore the resentments, motivations, and cultural outlook from which those moves derive?

I was scheduled to show a masterpiece of Italian neo-realism in my world cinema class, a heart-breaking slice-of-life story about desperately poor workers in Rome at the end of WWII. At the last minute, however, I decided to show a later and much more controversial film classic instead, The Battle of Algiers, a 1966 Italian film shot in the neo-realist style. It powerfully recreates, in quasi-documentary form, the uprising of the Algerian people against French colonial rule during the 1950s. Unflinchingly, it depicts brutal acts of violence perpetrated by both sides in the conflict.

During a particularly disturbing scene, in which Muslim women dressed as Westerners plant bombs in crowded cafes in the French quarter of Algiers, one of my students slammed shut the writing platform attached to his chair and jumped noisily to his feet. He stormed out of the auditorium. The rest of us finished watching the movie, which includes an equally upsetting scene of military interrogators torturing Muslim men, whose cries of agony are deleted from the soundtrack and replaced, ironically, by sad and haunting strains borrowed from the Saint Matthew Passion, Johann Sebastian Bach’s great oratorio dedicated to the martyrdom of Christ.

When I returned to my office after the screening, I logged on to a message from the student, which read, “I figured you deserve an explanation as to why I left class like I did today. With recent events as they are, to see a movie with such graphic depictions of Arab terrorism (even GLORIFYING such activities) INFURIATED ME. I could not sit there and watch more innocent people die.” He added, “I think it was in very poor taste to choose such a movie at a time like this.”

He was right. I’d been rash. It was too soon. I called him immediately to make peace, and we talked things out. He told me that he comes from a North Carolina military family, where patriotism is the highest form of virtue. In his opinion, the showing of that film was unpatriotic. I said I hope you’ll come to class tomorrow and explain your point of view. He did, and the result was a heated and probing two-and-a-half hour debate about the responsibilities of the artist in times of national crisis. I’ll never forget that discussion, or that student.

A couple years later, it was announced in the news that Defense Department officials had begun screening The Battle of Algiers at the Pentagon because of its remarkable insights into Islamic insurgency. Reading of this, I felt vindicated for my decision to show the film that day, although I continued to agree with my student that the timing had been wrong.

The point is, what art does that nothing else can do nearly so well is take us into the hearts and minds, even the blood and marrow, of those who are profoundly different from us. The arts don’t make us more human, for, alas, with all our imperfections we’re already as human as can be. But they make us understand, deep in our guts, what it means to be human. The arts are an essential vehicle for the fulfillment of Wake Forest’s pro humanitate vision, and they can be ignored, undermined, or downsized only at that vision’s expense.

Obviously, it’s better to become involved in the arts out of passion and curiosity rather than from a sense of obligation. Still, there’s something to be said for obligation. Last semester I was teaching my intro class on American art to 1900, which is capped at 25 students. On the first day I asked how many of them had signed up to get a divisional requirement out of the way. Approximately two thirds raised their hands, but they did so tentatively, fearing, perhaps, that I would disapprove of their motivation. Their anxieties were misplaced; I was delighted for the opportunity to introduce the history of American art to 18 undergraduates who otherwise would have gone through their college careers knowing little or nothing about it.

I ended the course, as I usually do, talking about one of the greatest artists ever produced by the United States, a 19th-century Philadelphian named Thomas Eakins. I regard his 1875 masterpiece The Anatomy Clinic of Dr. Samuel Gross, also known as The Gross Clinic, as the single most important painting to come out of 19th century America. It’s indispensable, and I’ll take a few moments to tell you why. Dr. Gross was an acclaimed Philadelphia surgeon and professor of anatomy. His students wanted to honor him with a portrait, so they approached young Tom Eakins, a prodigy who had trained in Paris after the Civil War and recently returned to his home in Philadelphia, where he specialized in paintings of sportsmen rowing on the Schuylkill River.

Eakins accepted the commission, but instead of contenting himself with the usual head-and-shoulders format, he went far beyond anyone’s expectations and created instead an enormous and electrifying work of visual art. As you approach it from a distance, its abstract masses of light and dark cohere into a storm of vivid detail flashing across the gloom of its massive surface. In a darkened amphitheater, the great surgeon pauses to make a point to the medical students arrayed before him on benches. At his side, a team of assistants huddles over the naked flank and buttocks of a faceless, anesthetized young male patient. The mid ground of the painting is crimsoned with blood, all the more conspicuously so because of the painting’s monumental scale. It assaults the eyes. Eakins, himself a student of anatomy, depicts with unflinching honesty the gruesome intricacies of the surgical procedure he had carefully witnessed. Raking light from above spills down on the leonine Dr. Gross, clearly no ordinary mortal. He becomes, in Eakins’ treatment, a titan, dark and brooding, his brow furrowed in thought, his grizzled gray hair springing wildly from his head, his fingers slathered with his patient’s blood.

When shown the finished portrait, Dr. Gross was appalled. It made him look like a butcher, he complained. He cursed Eakins. The public did the same. When the painting was exhibited at the 1876 Centennial world’s fair, they jeered, calling the artist a brute, a menace to society. His career never recovered from the blow-back in those days, unlike today, notoriety was not an artist’s best friend. He continued painting masterpieces for the next three decades of his life, but in relative obscurity, which should come as no surprise, given his adamant refusal to prettify his subjects. In retrospect, however, we can see that Eakins, with the intensity of his gaze, was our country’s first true realist. Realism in American painting, literature, drama — and a medium that hadn’t even been invented yet, cinema — all derive, in some measure, from Eakins’ bold commitment to showing the dark or seamy side of everyday life.

When the painting was first displayed at the Philadelphia world’s fair, outraged members of the public and press demanded that it be taken down. It was unfit, they said, to be seen by decent men and women. These critics felt that it insulted their city or, worse, America itself. After all, the Centennial exposition was meant as a celebration of the hundredth birthday of the United States and its glories, and Eakins’ blatant reveling in ugliness was an affront. They had no qualms about urging censorship of art that didn’t sit well with their cherished patterns of belief.

Some things never change. Today there are those who want to ban objectionable books from public libraries or shut down government funding agencies, such as the NEA, that support art of a controversial nature. I urge you, however, not to villainize these folks or trivialize their point of view. Their concerns are genuine: art does disturb the peace and therefore should be feared. The fact of the matter is, if the arts never upset us or caused offense, they’d fail to accomplish what may well be their most important role in a free society.

Let’s go back to the JFK speech with which we began. President Kennedy argued that a nation must be judged not only by its economic, diplomatic, and military strength, but also by the strength of its arts. I would use the same logic to say that no school can legitimately claim a place in the upper echelon of universities without a top-tier program in the arts. It’s impossible to have such a program without students and faculty pushing boundaries and resisting complacency, not only the public’s but their own.

It takes courage to step outside ourselves, to depart from the tried and true, the familiar; to get up from the sofa and change the channel. Professors and students alike need to set difficult challenges for themselves and overcome their inertia to meet them. In the case of professors, this means bringing their scholarly or creative work into the light of day — or the light of the theater, concert hall, or art gallery — and risking disapproval or outright rejection by their peers. If your professors put you through hoops in the classroom without demanding the same for themselves outside of it, a double standard is in play, and I don’t care how inspiring they may be as teachers, they’re not providing you the quality education you deserve.

For students, stepping outside the bubble might mean taking electives far from their home major, or simply wandering into art shows, classical music recitals, black-box productions, or other domains of art where they may feel strange, out of place, unsure of what’s going on. It might also mean reading dense, difficult academic writing about the arts, the kind that can make your brain smart-and here I’m using the term smart not as an adjective meaning intelligent but as a verb meaning to sting. In other words, you should periodically work your way through challenging prose about art as well as expose yourself to art that is challenging.

If after four years at Wake Forest you can boast of never missing a home basketball game but can’t remember attending a single poetry reading or taking a walk through the woods to visit the Reynolda House museum of art, you’ve squandered great opportunities for your own mental and emotional enrichment. Personally, I don’t think you’ve done justice to your college education unless you’ve not only seen but also vigorously debated with your friends the meaning of film classics such as Citizen Kane, Battle of Algiers, and Bicycle Thief — the movie I was planning on showing that day. Like so much else available to you on campus every semester, these are life-changing works of art, and you — not your professors, not the administration, not the Registrar, but you — need to make yourself confront them, in the classroom as well as outside of it, in order to become a genuinely educated citizen of the modern world.

Our thoughts are too easily congealed these days, our emotions blocked by routine and habit and substitute satisfactions dangled before us in the marketplace. The arts can help us break free and get things moving. Art, said Franz Kafka, is an “axe for the frozen sea inside us.” The metaphor is perfect, because it suggests that disturbing the peace-chopping up the frozen sea within-also creates peace, the freedom and relief that come from restoring our inner flow.

Yes, art disturbs the peace. Gently in some instances, violently in others, it draws us out of ourselves, out of our small-minded self-absorption, and makes us see, hear, feel — and understand — the world anew. As a nation, we can hardly do without the arts. As a university, we can only grow stronger because of them.

Categories: Happening at Wake, Research & Discovery

Wake Forest News

336.758.5237

media@wfu.edu

Meet the News Team

Headlines

Wake Forest in the News

Wake Forest regularly appears in media outlets around the world.