Sociology Class Sends Students into Community

Joanna Kociecki’s group decided that Bojangles’ was probably the best option for a part-time job to supplement a $272 a month welfare check and settled on an apartment nearby in public housing.

Joanna Kociecki’s group decided that Bojangles’ was probably the best option for a part-time job to supplement a $272 a month welfare check and settled on an apartment nearby in public housing.

Classmate Anthony Nicastro and his group had more choices when looking for a place to live using a $390,000 annual income. He found a luxury home on the ritziest side of town and enrolled a seven-year old in an expensive private school.

Both Joanne and Anthony are Wake Forest University students taking part in “The Poverty Project,” a class project for Sociology 151 taught by Assistant Professor Angela Hattery. Each student in the class was assigned to a fictional family. The social class groupings ranged from a two-parent, upper-income family to a single-parent family on welfare.

“The project is designed to illustrate social class stratification and some of its outcomes for young families,” said Hattery.

“I want them to see that social class stratification affects the house you live in, the school your kids attend, the food you can afford to buy” she said. “I can’t make them go live there for a month, but this is the closest I can get to have social class mean something to them.” Hattery will include the project in her class next semester, too. The “Poverty Project” ties in with her research specialty-job and family conflict. She has published numerous articles on the subject and is currently writing a book.

One lesson in social class differences sank in quickly when the lower-income families realized that the upper-income family had budgeted more ($25,000) for a vacation than their families’ annual income.

“I think that this exercise, where they actually had to budget money and report on it, made social class differences much more real to them than simply reading that the average income for a single mom is under $20,000, while the upper-class may earn in excess of half a million per year,” said Hattery.

In general, students gained a much better feel for the myriad of ways in which social class affects peoples’ day-to-day lives. Students were surprised at how much the basics cost, including child-care for those families that needed it. Other students commented on the limited job opportunities for the lower-income families because of education level.

Although some of the fictional families had only one parent, all had two children, ages four and seven. First, the groups of 7-8 students had to go out into the community to find an appropriate job for the fictional parent or parents. They were limited by the descriptions of the most likely occupations to be held by members of each social class as described in their textbook. So, the lower-income group could only consider unskilled labor and service work, while the upper-middle class options included professional and technical fields.

After selecting an appropriate job and finding out the probable pay, the groups had to find housing for their “families” and figure out transportation. For the lower-income families, renting apartments close to work was the best or only option. A middle-income, single-parent family was able to afford a three-bedroom house.

For the welfare family, transportation was an easy decision-the bus. The lower- income, single-parent family wrestled with whether to buy a used car or rely on the bus and opted for the greater cost, but also greater convenience of the car. The upper-class, two-parent family selected a Range Rover and Mercedes as their two vehicles.

Once the job and housing were selected, the groups had to choose the best child care facility for the younger child and visit the school the older child would attend (based on location of housing.)

For the lower-income, single-parent family, housing and childcare were the two biggest budget items. Another lower-income family decided to have the mother stay at home to take care of the younger child during the week and work a part-time job at Burger King on the weekends.

“Child care eats up a lot of your budget, almost 20 percent,” said a member of a lower socioeconomic group.

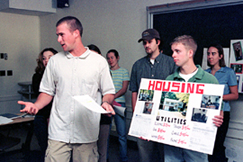

The groups took photographs of the housing, schools, and child care facilities they found for their “families” and made class presentations in late November.

To complete the project, the students also had to develop menus for meals and shop for a week’s worth of groceries based on the weekly income of their “family.” The money for the groceries came out of the students’ pockets and the food was donated to Samaritan Ministries. Several students delivered the food and received a tour of the soup kitchen and homeless shelter.

“It was a huge shock not to be able to just throw everything into our basket when we went grocery shopping,” said sophomore Katie O’Brien, assigned to the lower-income, two-parent group, who budgeted $50 per week for groceries. Another group found that they could save 40 to 50 percent if they bought generic brands.

“I also saw how education can make a difference. If the father in our family had a college education, he could have made more money, even working at the same place,” said another student, Samantha Ertenberg.

“The most eye-opening thing is, she doesn’t have very much money. Like Christmas gifts, can she afford them for her kids?” said sophomore Sarah Shivers, who was assigned to the lower income, single-mother family.

“I did not have a good sense of how much things cost and how little was left over,” said Kyle Covington, a member of the lower-income, two-parent family group.

“The only extra we added was cable TV.”

Categories: Community Impact, Experiential Learning

Media Contact

Cheryl Walker

media@wfu.edu

336.758.5237