Seven Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Your Mother (So Dear)

Is the date on Wait Chapel wrong? Jenny Puckett ('71) explains the secrets of the cornerstone and more things you might not know about Mother So Dear.

Jenny Puckett (’71) returned to teach Spanish at Wake Forest in 1995. She and husband, Jody (’70), are the parents of Lee Puckett (’00). She delivered this address on April 8, 2009, as part of the University’s Last Lecture Series.

There’s no way to be sure about this, but I suspect that most people who are invited to give a Last Lecture may experience one brief moment in which they hope that it’s not a large hint of some kind. But in truth, it is such an honor to be invited to speak in the Last Lecture series, and I sincerely thank you for this opportunity, and most of all, for being here tonight.

When I first received the invitation, I had two extreme reactions: extreme gratification and also some pretty serious intimidation. The intimidation had to do with the task of narrowing down those things within my experience which have become distilled into something important enough for a last message. Well, it didn’t take long to realize that in the future, it wouldn’t be an earth-shaking matter if people remembered a particular fact or single skill from any of my Spanish classes, although that would be nice! Instead, what quickly became clear is that no matter what we study or teach or are interested in, we are all people of Wake Forest. And in the end, that made the choice of the topic very easy. The subject is us.

For all of us in the Wake Forest family, one thing that defines us, and of which we are rightfully proud, is our sense of community. I never get tired of that moment, at the conclusion of the playing of our alma mater, when students roar out the last line, Mother So Dear. Because, although “Dear Old Wake Forest” works us to death sometimes, we all love Mother So Dear, yet we may not know exactly why we feel such a passionate affection for the old girl.

Maybe it’s because of the intensity of the experience: all of the elements of daily life here on campus are so compelling, demanding, enlightening, exhausting, and stimulating, and at times, thrilling. And sometimes, a part of why we love Wake Forest is because we sense that we’re surviving it. But there’s something else here, too. It comes from our surroundings; we walk through this place, and sometimes it gives us the feeling that we can faintly hear the music of the past. And the only way we can understand where we are is to take a look at where we’ve been.

So, instead of giving a lecture tonight, I would like to invite you to take a walk with me around our campus. Our hike will take us to seven different places, some of which are just not considered landmarks. At each place we’ll take some snapshots, look at it from another point of view, and perhaps see it a little differently the next time we pass by.

I.

Our first stop is a destination in time and space, but we can walk once we get there; we’re going to visit the decade of the 1940’s, in the town of Wake Forest, NC. Why the 40’s? Because we had reached the fork in the road. All of you know that Wake Forest didn’t always live in Winston-Salem, but what you may not know is that three sweeping changes were being created by urgent conditions. I submit to you that everything that we know as modern Wake Forest depended on the outcome of three elemental shifts that occurred in that one decade; each one was a wrenching and difficult transition, and one of them was the biggest gamble of them all. These things occurred at Wake Forest in a single span of less than ten years, closer to six years, really. And from each one of these changes there could be no going back.

When dawn broke on the decade of the 1940’s in the little town of Wake Forest, the 106-year-old campus was showing some bruises. There had been a series of mysterious and devastating fires during the previous decade, which had destroyed or damaged several buildings, and it was exceedingly difficult to find money for rebuilding during the Great Depression. Additionally, one piece of the campus was already breaking off and preparing to move away: in 1939, the trustees had agreed to move the two-year medical school from Wake Forest to Winston-Salem, so that it could affiliate with Baptist hospital to become the four-year medical school known as Bowman Gray School of Medicine.

But at the beginning of the 1940 school year, almost everything else was as before: the all-male student body loved its magnolia-covered campus. The young men called it their “calm bachelory”. David Fyten, in our alumni magazine, wrote that it was where “intellectual giants and kindly townsfolk had nurtured generations of small-town and farm boys.” As in years past, they got off the train, moved in, got to know everyone else on campus, went to classes and chapel, hung out at the old well, respectfully greeted their professors before class, had active social lives, (traveling frequently to Raleigh to scout for female companionship at Meredith and Peace Colleges), and they loved their sports.

But in that winter of 1941, the war came to Wake Forest. The times, already frightening, became financially even more trying. In the words of the 1942 Howler yearbook, “The gravity of the situation was made clear to every man. Many students had to leave almost immediately for training camps; many others signed up for service after graduation. The rest remained in school and waited.”

Arch on the old Wake Forest campus

But with all the shattering changes, the war brought in another, more acceptable necessity: the admission of the first regular-admission women students in 1942. When the announcement of the female invasion was made, the yearbook writer said, “When the news began to sweep over the campus, everybody decided that that indeed was a momentous day. There was opposition at first — antagonism toward this new idea, this ‘radical’ idea that would change Wake Forest forever. But then the real motive was revealed: Without the admission of women, there might not even be a Wake Forest in a few years — with the enormous exodus of men to the armed forces. The students were reconciled. Gradually the invaders subdued the vanquished.”

But despite the admission of women in 1942, the times became even more fearful; enrollment in 1944 fell to 328. In order to secure capital to keep the college running, Wake Forest contracted with the US Army to house the Army Finance School on the campus. The soldiers and officers pretty much took over the campus. The students wrote, “By December, we had given up our cafeteria, our gymnasium, our dormitories, our just-completed music-religion building, and two of our classroom buildings. Five fraternities, forced out of Simmons Hall, had to find new houses. We found ourselves deprived of home basketball, taking physical education outdoors, eating in restaurants downtown, and rearranging our mode of life.” The yearbook editors even muttered darkly that the brand-new female contingent on campus seemed to be looking a little too long at all those men in uniform.

Even after a flood of veterans came back in 1946, financial troubles continued until, in that same year, the Board of Trustees accepted the offer of the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, backed by the Reynolds, Gray and Babcock families, to move the entire campus 107 miles west/northwest to Winston-Salem. That announcement struck the little town terribly hard, since there was little or no separation between the campus and the town; practically everyone in the town was linked to the College. David Fyten wrote that it was going to mean “pulling up roots that were more than a century old, and pulling a heart from its body.” But, it would mean a new world for Wake Forest.

Harry Truman breaks ground on the new Wake Forest campus

Construction began after the groundbreaking on October 15, 1951, with President Harry Truman presiding over the ceremony. His presence here that day was noted around the world because he also used the occasion to give a major foreign policy speech. And now it was time to build on the 320 acres of prime land that the Babcock family had signed over. Do you remember your impression of the campus when you first saw it? That classic beauty and orderly layout were the inspiration of Jens Frederick Larsen, the architect. As Fyten describes him, he was a brilliant choice because first, he rejected trendy, post-war modernist architecture, the glass-and-steel monstrosities which were in fashion at the time, in favor of the neoclassic Georgian beauty that we enjoy today.

He thought that the transition from old to new campuses would be easier if there could be visual continuity of buildings and landscaping. And so, after studying this terrain, he decided that the campus should be laid out on an orderly grid, with the axis being a straight, symbolic line that would begin to the north at Pilot Mountain, representing nature; the line then ran south, straight through the steeple of Wait Chapel, representing God, and then continued south through downtown to the Reynolds Building, representing man and his commerce. I believe that Larson’s philosophies about beauty and symbolism still speak with silent eloquence.

Are you ready to walk around the construction site? As you begin walking, you’ll see that the library has gone up first: you’ll see some other buildings magically go up before your eyes; you’ll see the bones of Wait Chapel, and, when the buildings are nearing completion, you’ll also get to see the planting of the magnolias on the Mag Quad.

II.

Now let’s walk up to Wait Chapel and take a closer look at the right hand side. Have you ever wondered what may be inside this cornerstone? Like many important and historic buildings, Wait Chapel’s cornerstone notes the date the building was dedicated, and also has a time capsule buried inside. After tonight, you’ll know that the number on the stone is not a typo, and you’ll also know what the capsule looks like, and what is inside it.

Construction of Wait Chapel

Here we are in October of 1953, the day of the laying of the cornerstone. The laying of the cornerstone was planned by Dr. Henry Stroupe, whose family was one of the many faculty families that had to put life on hold for ten years while we were between campuses. In 1946, a week before the Stroupe family was all set to buy a new house in Wake Forest, the announcement of the “Removal” was made, and so the family rented for ten years until their new house on Faculty Drive was ready for occupancy. Dr. Stroupe and his wife Elizabeth still live in that beautiful house. As chair of the history department, it fell to Dr. Stroupe to plan for the time capsule that would be cemented into the cornerstone forever; he had to design the box itself, and decide upon its contents. The ceremony was planned for 1952, but construction delays put the dedication ceremony a year later.

The capsule contained, among other things, newspapers of that day from the major cities across North Carolina, a King James version of the Bible, some brick fragments and a container of soil from the old campus, a magnolia leaf, some presidential pictures, and a list of the contents. But the most unique addition was a letter from a little boy. Dr. Stroupe’s 8-year-old son Steven had written a letter, addressed to “boys of my age in the future.”

A month ago, I spoke to that little boy, who is now a recently retired chemist in the Chicago area. This still-young man vividly remembers seeing workmen solder the copper box closed; however, just before it was sealed forever, the architect reached into his pocket for his signature time-capsule additions: he drew out a handful of BB’s and a newly minted 1953 copper penny. Steven later had another unusual link to the building in which his letter is buried: after he graduated from Mother So Dear in 1966, he soon after married Jane Sherrill, the local girl whom he assisted in December of that year to organize the very first Christmas Lovefeast; that first year of the Lovefeast, it took place in Davis Chapel, with a small group of friends. Today, in Wait Chapel, it is the largest Lovefeast in the world.

You know, it’s not unusual when a university builds a building. But when a school manages to construct an entire new campus, and then transplant itself physically, intellectually, spiritually, and with almost every bit of its campus community intact, that is a singular event. Today, this simply could not be done. Even now, although I’ve read about it, studied it, and interviewed people who were there, my mind still cannot grasp the sheer enormous size of that particular leap of faith, which was taken by so many people. I must admit to you that it’s still just about my favorite miracle.

III.

Now, let’s walk over to Tribble Hall. You need to know how perfect it is that this particular building is named Tribble. You and I both know how Tribble Hall is: this innocent-looking exterior doesn’t even hint at how interestingly chaotic the interior is. It’s very fitting that this building is named for the most controversial of Wake Forest presidents, Harold Wayland Tribble, the 10th president of Wake Forest. An ordained Baptist minister, theologian and scholar, he was the president chosen in 1950, after the decision to relocate, and the trustees selected him to make the move a reality.

I hate to use hackneyed phrases, but this man, it can truly be said, was larger than life. He had to be. He was made captain of a very unwieldy ship that was headed for some stormy weather. At different points in his career, he was both beloved and vilified. He was praised and admired, and yet he came very close to being fired on more than one occasion. Every single one of his major constituencies experienced the love-hate thing with him: students, faculty, alumni, members of the Baptist State Convention, trustees, major donors, you name it. During the same week that Dr. Tribble retired in 1966, Russell Brantley, a former director of communications of Wake Forest, wrote, “There must have been times during the past 16 years when Dr. Tribble felt like the general at Custer’s last stand, but he always managed to escape with scalp and dreams intact.”

Dr. Harold Tribble

What dream? When Dr. Tribble became president in 1950, he said in his inaugural address that for us to become a university was “inescapably implicit in the removal and enlargement program.” There were many opponents to relocating the college, and there was always the problem of money. The cost of the campus went from an estimated $6 million in 1950 to $19.5 million six years later. But Tribble was a tireless fundraiser, at a time when he was constantly beset by several groups of enemies. Brantley said that, “Most of his problems stemmed from opposition to the move, fears that he favored de-emphasis of athletics, and concern among some members of the Baptist State Convention that the college was losing touch with the denomination that founded it.”

And, Tribble had one more enemy: his own personality. People claimed that he was bad for faculty morale, and that he was a dictator. But even his enemies never denied that he worked the hardest for Wake Forest when the rumblings of opposition were being heard the loudest. I agree with Russell Brantley when he said that “No one has ever disputed his enthusiasm, his capacity for work, and willingness to fight,” but I would add that perhaps his heaviest lifting could have been his willingness to fight for a new governance relationship between the school and the Baptist State Convention. Tribble’s fights with them over that issue formed the basis for discussions that would eventually lead us to financial and intellectual independence.

My mentor and favorite professor, Dr. Ed Hendricks, recalled that Tribble was an astonishing fund raiser. Once, when he headed up to the North Carolina mountains to get a small cash gift from an old timer, he came home without any money, but instead had secured the deed to 100 acres of prime oak forest. That wood became the beautiful paneling of Wait Chapel, as well as gracing many formal rooms and lecterns all across the campus. But in the meantime, he had to get the ship docked safely in Winston-Salem, yet even as it sailed into port in June of 1956, there was a dispute among the trustees concerning whether to remove him as president. It caused his wife to wonder aloud whether she should even unpack.

But he made it and we made it. Was he a dictator? I don’t know. What matters much more is that Tribble was a fearless trailblazer. And, he was a minister, after all. We’ve heard anecdotes about what it was like to deal with him. Not only was he intimidating in person: they say that even the letters he wrote could be pretty scary. He apparently could make a letter roll with thunder. His letters, like him, were often full of energy, righteous indignation, bluster, talk of consequences, and these fire-and-brimstone epistles were signed, “Your brother in Christ, Harold W. Tribble.” Now let’s walk up to Reynolda Hall, and we’re going up the steps to the back patio and look out over the Mag Quad.

IV.

Here we are under this nice-looking balcony. Why stop here? Because as if it were not enough that Dr. Tribble had already been fighting off dragons of various sorts, wouldn’t you know that at the beginning of only the second academic year on our new campus, all Hell broke loose. In November of 1957 there was a student demonstration right here on the patio that was so large and so loud that we made the pages of Life magazine. And where do you think the students staged their protest? Right outside of Dr. Tribble’s office balcony. I guess the students figured that even he couldn’t write that many letters.

The Life magazine writer called this protest “a collision between an irresistible attraction and an immovable objection.” But, why were the students protesting? Well, it seems that on a November Wednesday of 1957, the Baptist State Convention re-affirmed an edict that said: There will be no dancing on the campus of Wake Forest College. That’s right, no dancing. Now, it goes without saying that they had already banned sex on the campus, which makes perfect sense. It looks so much like dancing. So, how did the Wake students react? That same night, they burned in effigy the Baptist minister who pushed through the edict, the Rev. J.C. Canipe.

WFU students dance in protest

The next day, at 11 a.m. during required chapel, all the students were awaiting a pre-arranged signal which almost unbelievably was communicated without the use of a single cell phone. When the students heard an alarm clock go off in the back of the chapel, all 1,900 stood up, turned their backs on the speaker, and marched out of the chapel, and straight down to this patio. They pulled a jukebox out of the snack shop, started dancing, cut classes for the rest of the day, and danced until after dark when, apparently, quite a few of them went over to Thruway Shopping Center to form a conga line. It could have been the first Wake n Shake!

Two songs were extra popular that day: Wake Up Little Susie and Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin On. One woman student told Life magazine, “We ought to go and dance with those old men and see if they get all shook.” Now, I don’t know about you, but personally I was shocked that a Wake Forest woman would be that impertinent. One of those young protesters dancing was Murray Greason Jr. who grew up to become the chairman of the Wake Forest board of trustees and a member of our law school’s board of visitors. Last year, he received our university’s highest honor, the Medallion of Merit.

V.

Let’s go down the steps toward Benson and we’ll take a look at the new Shorty’s. Why the name? Shorty Joyner opened up a restaurant on White Street in old Wake Forest in 1916; it is still open. As Fyten says, “it was a smoky hamburger joint and pool hall that was a den of iniquity to the righteous but a perennial heaven on earth to students.” Two of my dear friends, Dot and Maurice George, remember Shorty’s from their student days, but only Maurice remembers it in detail because only he was allowed to go in there; the female students were forbidden to enter. That may have had something to do with the pool tables in the back room. Regarding the menu, Maurice says that the hot dogs were small, delicious, and, in the days before we were too picky about artificial food coloring, they were bright red. There were two slogans for the place: “Meet me at Shorty’s” and “Heaven on a Bun.”

'Shorty' Joyner

It apparently was such an appealing hangout that it had a negative impact on academics. You may not know that one of America’s most famous actors, Carroll O’Connor, was a Demon Deacon before the Big War; he was later Archie Bunker, America’s most famous bigot in the comedy series All In The Family. O’Connor once said, “Off I went in September 1941 to meet ‘Shorty’ Joyner and became a truly dangerous nine-ball player. I was a wretched student, utterly disinterested in the classroom learning situation. When I resumed college in 1947 at the University of Montana, I could transfer only one semester’s credit in English gleaned at Wake.”

As a mature actor, O’Connor would faithfully render the stupidities of racism, and here is what this native New Yorker said of his three semesters in Wake Forest; “I learned a great deal about North Carolina and its people. Believe it or not, one heard many, many whites even then expressing a certainty — yes, and an anxious wish — that the segregationist culture would soon wither away.” He continued: “I last saw Wake in 1945. I was a merchant seaman then, a fireman on an oil tanker, and we were lying useless in Miami with a broken boiler when Truman dropped his persuaders on the Japanese. I quit my ship and found a fellow who was driving to New York, and when we came through Wake Forest we stopped at Mrs. Wooten’s guest house on Route One. I roamed around the town that evening saying hello here and there, and I was touched and surprised almost to the point of disbelief that so many people remembered me, and not only remembered me, but welcomed me back, welcomed me home with love.”

VI.

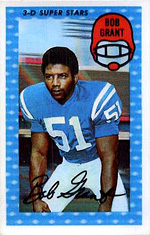

Okay, now let’s walk over to the football practice field. A lot of great athletes have practiced and are still practicing right here on this turf. All of you have heard of Brian Piccolo, but one of his teammates that you may not know is Robert Grant. Robert Grant, Kenneth (Butch) Henry and Willie Smith entered the university in the fall of 1964 as the first black student-athletes at Wake Forest. It should be noted that the University of Maryland was the first school in our conference to recruit an African-American player, Darryl Hill, the year before, but Wake Forest was the first major college in the South to integrate its football program.

v

Bob Grant

Recent documentaries have mentioned a player at SMU and a player at the University of Kentucky as being the first black players to integrate Southern universities, but by the time they entered their respective schools, Bob Grant and Butch Henry had been here for two years, paving the way for future Demon Deacon greats. Robert Grant was an outstanding defensive end for the Deacs, and received all-conference honors. Just one month ago, in Riverside, Calif., on March 7, Robert Grant was given the Trailblazer Award by the African American Ethnic Sports Hall of Fame. He was cited for the following: 1) He was the first black player south of the Mason-Dixon line to play for any of the major colleges or universities; 2) He was the first black All-Conference player in any of the Southern conferences; 3) He was the first black player from a major Southern university to be drafted by an NFL team, the Baltimore Colts; and 4) He was the first black player from any Southern university to win an NFL Super Bowl Championship.

When my husband and I talked to him in February, he reminisced about his days as a trailblazer in the effort to integrate college sports. Although his experience here was not a perfect one, he did remember his days here with great affection and understandable pride. When I asked him if he would like me to pass on a message from him directly to you, this is what he said: “Tell them to live courageously. It’s a pretty scary thing to do at times, but I highly recommend it, and it’s never too late to start.”

VII.

Now, let’s hike the last leg, over to BB&T Field, where we’re going to stop at the entrance to the football stadium. Did you know that the Demon Deacon was based on a real person? Down through the years, there have been many men, and two women, who have represented us as the Demon Deacon. Allie Hayes was the original, in 1932. He played right end for the football team and ran sprints and high hurdles for the track team. But he was chosen by the band director to be a drum major, based on his good looks and his presence. One day, Neville Isbell, the band director, asked Allie to go with him up Faculty Avenue to one of the Baptist minister’s homes. The minister’s wife met them on the porch, and she brought out the ministerial uniform of the day: a swallow-tail coat, top hat and cane. It fit him perfectly, and from that moment on he marched with the band as the leader and drum major.

The Demon Deacon

It wasn’t until 10 years later, in 1942, when Jack Baldwin, on a dare, dressed up as the Deacon and rode onto the football field on the back of the Carolina Ram, that we had our sports mascot. After that day, the Deacons never again played without our mascot.

Consider this wonderful figure, and consider what it is NOT. Folks, in our early days, when the students of Wake Forest wanted a mascot, they did not need to borrow the glory from some other school; they did not need to pick out some sort of creature to represent us: like a wild animal, or a wild bird, or a farm animal. We had the real deal. The Deacon was organic; he came from the people those students knew and the lives that they lived. He’s real, and he’s uniquely ours. So the next time you’re at BB&T Field, go up close to the statue of the Deacon and look closely at the spark in his eye, at his wonderful, big hands, and especially, look at the long step he’s taking. Do you know how long that step is? It is 107 miles long. And what an amazing journey it has been.

Conclusion

And now let’s stop walking, and you can rest your feet for a moment. It’s time for me to read the Trail Marker which says, “Last Lecture. Get to the point.” And the point of a Last Lecture is so bittersweet; I now must imagine that this is my last opportunity to tell you something important. What would I have you remember that I said?

1) It would be this: I would ask that you consciously and deliberately embrace the legacy that rightfully belongs to you as Wake Forest people, not only because it is a precious and enviable thing, but also because it is a living history of which you are a part. Our history lives and goes forward through you, which is why it is so important that you know our story, the incredible journey of 175 years that brought us here. And then, in whatever way you think is appropriate, keep these things from being forgotten.

2) The other thing that I would ask is that you consciously and deliberately accept the graduation gift that your Mother (So Dear) is going to give you on that May Monday when you receive your diploma. It’s actually two gifts, two great and simple gifts. They are two two-word mottos that you carry with you into your future lives. The first one is the unifying ideal of our University, which was lived out and brought here by the trailblazers of the past: Pro Humanitate, “for humanity.” No one can say where all of you will end up, but the chances are strong that those of you who end up the happiest will be the ones who find a way to be “for humanity,” and heaven knows, humanity needs it.

The other two-word motto lives in your heart alongside the first one, but don’t leave it there. It needs to be on your lips, every season, every year, and you know exactly the one I mean: Go Deacs!