Not your typical fish out of water

Unlike the vast majority of fish that inhabit the oceans, rivers and streams of our planet, the amphibious mangrove rivulus is comfortable out of water.

Scientists previously discovered the mangrove rivulus could breathe through its skin, enabling it to live on land in a relatively moist environment for up to 66 days! What has not been addressed to date is how the 3-inch rivulus moves across the ground once it gets there.

This is where Benjamin Perlman, a Ph.D. student at Wake Forest, comes in.

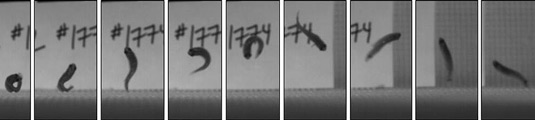

Perlman is the lead author of a new study that shows the rivulus uses a strong jumping technique to traverse land while looking for food, avoiding predators or escaping poor water conditions. This consists of a powerful tail flip, whereby the fish orients its body in the direction it wants to go and then flips its head backwards over its body. Perlman said the rivulus can do two or three somersaults through the air.

Studying the flipping ability of these fish helps scientists understand the evolutionary changes that helped fish make the transition from water to land millions of years ago.

To get an idea of how effective a rivulus really is at moving on dry ground, Perlman and his team put it to the test against a juvenile largemouth bass.

The largemouth bass uses a c-jump, a technique many fish use to return to the water when stuck on land. The c-jump involves a fish making the letter C with its body then pushing down with its head and tail, propelling it upward. Because the technique generates force mostly in the vertical direction, Perlman said a c-jumping fish essentially goes up without moving forward or backwards.

His team filmed juvenile largemouth bass and mangrove rivulus jumping off a force plate when prodded with the end of a stick. They then compared the force of the jumps. The results confirmed their hypothesis that the rivulus has a much stronger jumping technique on land than the largemouth bass.

“The only time you see a largemouth bass on land is when it is stranded or chasing a food item and ends up out of the water, which is extremely rare,” Perlman said. “They basically just thrash about. The rivulus seem calm on land. Its movements are very directed.”

Perlman works with Wake Forest undergraduates on a class trip to Belize.

Perlman’s research grew out of a project his faculty advisor Miriam Ashley-Ross started to document the different types of fish in the world capable of moving across land. Ashley-Ross, an associate professor of biology at Wake Forest, said Perlman’s work proves that different populations of fish do in fact differ in jumping performance. She added that his new study, which he presented July 5 at the Society for Experimental Biology Meeting in Valencia, Spain, and again in Barcelona, Spain, on July 11 at the International Congress of Vertebrate Morphology, will go a long way in helping researchers to understand the biomechanics of the tail-flip jump.

Perlman said perhaps the most interesting aspect of his research is how it can be applied to the evolution of other species. He said the rivulus is an ordinary looking fish without any obvious characteristics suggesting it would be able to move efficiently on land.

“Going back into the history books, 360 to 380 millions years ago, fish had these modified appendages where their fins started to evolve into limbs. These fish don’t have anything like those,” he said. “It kind of makes you rethink which animals in the fossil record might not have a certain form that would suggest efficient locomotion on land, but might be able to function well in an unfamiliar habitat.”

Categories: Experiential Learning, Research & Discovery

Media Contact

Wake Forest News

media@wfu.edu

336.758.5237