Honoring 'Strength, Resolve and Legacy'

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of African American women integrating residence halls

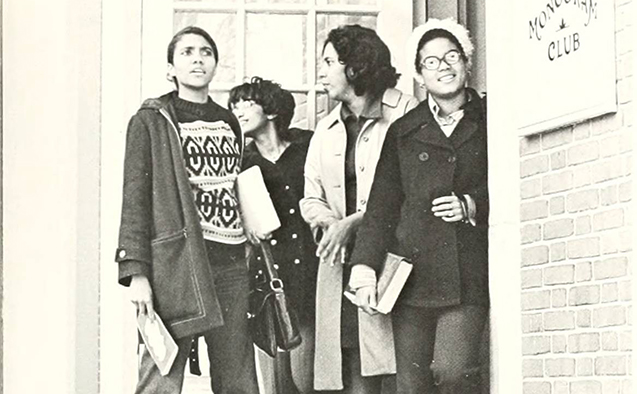

When they moved into a women’s residence hall in 1969, Beth Norbrey Hopkins and Deborah Graves McFarlane simply wanted to obtain a good education and weren’t thinking about making history as the first African American women to come to Wake Forest as resident students. But they did.

So did Awilda Gilliam Neal and Linda Holiday, who moved into a women’s residence hall in the spring of 1970, and Winston-Salem native Camille Russell Love, who enrolled as a day student that same semester.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the women moving into the residence halls, Wake Forest held several events Jan. 30-Feb. 2 themed around Strength, Resolve and Legacy, including a program and reception on Friday and panel discussions, a luncheon and a second reception on Saturday. The women were also honored during a meeting of the Wake Forest Board of Trustees, at the men’s basketball game and during Sunday worship service at a local African American United Methodist church.

“The extraordinary weekend planned by the University demonstrated that, irrespective of color, all students matter to Wake Forest,” Hopkins said. “Black alumni departed from the events filled with joy and high expectations for moving forward in the area of diversity.” The celebration helped to heal some old wounds, reconnected alumni who had not returned to campus in 40 years and provided a pathway for a new level of understanding between the University, students of color and alumni who look like me.”

Hopkins, McFarlane, Neal and Russell all graduated from Wake Forest in 1973 except for Holiday, who transferred to and graduated from nearby North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro.

“The celebration helped to heal some old wounds…and provided a pathway for a new level of understanding between the University, students of color and alumni who look like me.” Beth Hopkins

Welcome back

“Tonight, we gather to honor the courageous women who helped build a strong residential community here, and we also recognize those who came before them, the day students at Wake Forest,” said Wake Forest President Nathan O. Hatch at Friday’s program in Byrum Welcome Center. “These women are the ones who helped us change the trajectory of our past and pointed us to a more inclusive future.”

Hatch ended by saying the University must redouble its efforts “to make Wake Forest a genuinely welcome place for all.”

José Villalba, vice president for diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer, also spoke, heralding the women for opening the hearts and minds of the community “while also holding the door open for those who would come behind them. They were not the first African American women on campus … and they were not the last.”

Friday’s program was emceed by Mütter Evans (‘75), who became the second African American woman in America to own a radio station when she bought WAAA in Winston-Salem at age 26 in 1979. “This is an evening to acknowledge, remember and uplift the journey of the African American women who led the integration of residence halls here at Wake Forest,” Evans said. “They accepted the call to lay their bodies, minds and souls in the midst of a space that until that time had not welcomed or provided refuge for African American women.”

After several student performances, Hopkins spoke.

“These women are the ones who helped us change the trajectory of our past and pointed us to a more inclusive future.” Nathan O. Hatch, Wake Forest president

“There were fewer than 30 black students at Wake Forest when we arrived,” she said after thanking Hatch and the University community for the celebration. “We were a fiery band of students shaping history without an intention to do so. We are thrilled to be here 50 years later and to have you share this weekend with us. We’re excited about the leadership of Wake Forest and are here to help you, Dr. Hatch, and the Wake Forest community fulfill your vision for future generations.”

Hopkins said the five women leaned on each other academically and emotionally while also getting support from their African American male classmates who often escorted them around campus at night. “Gentlemen, had there been no you, there would be no us. Thank you.”

See more photos from the weekend

School of Divinity Dean Jonathan L. Walton paid tribute to the women before Villalba brought them on stage and later invited all Wake Forest African American alumni to join them.

Panel discussions, speaking candidly

On Saturday, Hopkins, McFarlane, Neal, Holiday and Russell talked candidly during two panels — one moderated by Wake Forest Board of Trustees Past Chair Donna Boswell (‘72, MA ‘74), and one with current African American female students that was moderated by Kelly Starnes, (‘93, MBA ‘14), president of the Association of Wake Forest University Black Alumni (AWFUBA) and a member of the Alumni Council.

Though they shared some not-so-pleasant moments from their time at Wake Forest, the women said the experience was worth it because of the outstanding education they received and the lifelong friendships they made. They all said if they had it to do over, they would again attend Wake Forest.

Boswell said she felt blessed to share the stage with them. “Let’s be clear. I was very naive, and I know 50 years later I had no idea what they were experiencing,” she said. “I am grateful for this opportunity to ask the questions today that I should have asked in 1969.”

Linda Holiday

Holiday said she dreamed of attending Wake Forest as a young girl. “When I came here, I came from a high school that was predominantly white. It was a small school and we felt very safe,” she said. “The faculty were welcoming and had our best interests at heart. Speaking of being naive, when I came here, I expected the same treatment. But it was not all bad. There were some great times. We laughed together. We cried together. We all were very good friends.”

Neal wanted to attend American University in Washington, D.C., but her mother worked for President Harold Tribble who wanted her to attend Wake Forest. “He said he’d see that I’m treated fairly and that I’m awarded a scholarship,” she said. “When I entered Wake Forest in 1969, the black students were welcoming. The white students were polite, but they did try to look at my test grades when I received them to make sure I was not here on affirmative action.”

Love, already a parent when she enrolled, said the University offered the chance to restart her life, get an education and move out of her parents’ home. “My father was a politician, and he was very good friends with some Wake Forest patrons, Anne Reynolds Forsyth and Dr. Forsyth. He told them about me, and they said, ‘Fine. If she wants to go, we’ll take care of it.’ So I’d go to their house, take my grades and then pick up a check to bring back to Wake Forest. Dr. and Mrs. Forsyth told me it was important for not just the students but also for the faculty to understand that black students could sit beside white students and perform. We needed to demonstrate that we were capable and competent.”

Awilda Gilliam Neal and Camille Russell Love

McFarlane said the African American students at Wake Forest in the early 1970s were close-knit and traversed the campus together. “We moved in mass,” she said. “I really think to a certain extent we segregated ourselves. We ate together. We partied together. I remember one time coming across campus at night and there was heckling going on so I just turned around and went back and then I had an escort. After that we always had escorts. It was a family experience, being one and moving in mass.”

Hopkins said faculty struggled to understand the African American students and weren’t convinced that they belonged at Wake Forest. “Gradually the professors came around,” she said. “They realized we were not going to let anybody outwork us.”

The University’s African American housekeepers were of tremendous support to the students, the women said. They also acknowledged Ross Griffith for trying to increase the number of minority students on campus. Griffith worked in admissions during part of his 47 years of employment at the University.

Student voices

After their panel, three of the women were joined by student leaders Neicy Myers, Bria Johnson, Taylor Fowlks and Lelaini Fletcher, who said scholarship dollars factored heavily into their decision to attend Wake Forest. The students also said they’re receiving a good education but want to see more support for minority students.

Fowlks, a senior politics and international affairs major from Spartanburg, South Carolina, said most of the people she surrounds herself with look like her. “But I’ve pushed myself this year to go outside of that bubble to try to get to know people who don’t look like me or to try to see where they’re coming from and to learn about their experience and to see what they can teach me,” Fowlks said.

Myers, a senior sociology major from Scranton, South Carolina, said she still has classes in which she’s the only African American and drew applause when she challenged the University to not only increase the number of students of color, but also increase support systems to help them navigate at Wake Forest.

“I’ve pushed myself this year to go outside of that bubble to try to get to know people who don’t look like me…to learn about their experience and to see what they can teach me.” Taylor Fowlks, senior politics and international affairs major

Starnes thanked the students for their candor and asked how alumni could assist them. Love stressed to them that they belong at Wake Forest and joined her colleagues in offering support. Hopkins encouraged them to learn the art of forgiveness and not to let anyone steal their joy.

The panel ended with Donovan Livingston, assistant dean in the office of University Collaborations, performing spoken word. Livingston delivered the spoken word poem, “Lift Off,” about the hurdles black people must overcome in today’s education system, at a convocation of the Harvard Graduate School of Education. It became a viral sensation that has been viewed more than 13 million times.

Later in the day, a reception was held for them inside Angelou Residence Hall, named for Maya Angelou, a poet, author, actress and civil rights activist who taught generations of Wake Forest students as Reynolds Professor of American Studies from 1982 until her death in 2014.

“The events were a really nice milestone in our institution’s history and an opportunity for us to commemorate and acknowledge five women who, over 50 years ago, joined the University community,” said Malika Roman Isler (‘99), assistant vice president for inclusive practice. Isler worked closely with Villalba to plan the celebration. “We’ve been on a consistent journey to really be more diverse and inclusive, so last week’s events represented an opportunity for us to acknowledge what that experience was like for those five women and to look and reflect on how far we’ve come as an institution since that time.”

See the photostory:

Categories: Alumni, Enrollment & Financial Aid, Happening at Wake, Inclusive Excellence

Wake Forest News

336.758.5237

media@wfu.edu

Meet the News Team

Headlines

Wake Forest in the News

Wake Forest regularly appears in media outlets around the world.