Sociology class uses 1950 Census to create work history family trees

Gabi Overcast-Hawks

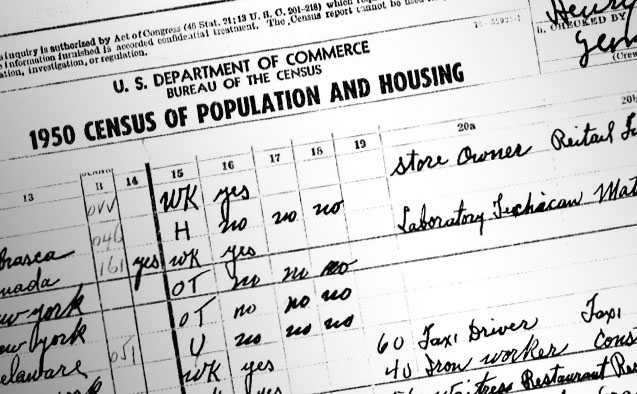

When Gabi Overcast-Hawks searched the 1950 U.S. Census records, she found her grandfather’s handwritten name, along with his mother and father and seven brothers and sisters. Place of birth: Carroll County, Virginia. Occupation: farmer.

Seventy-two years ago, one of 140,000 “enumerators” visited the Hawks’ home to record names, ages, occupations and other information about the family as part of the counting of Americans that has taken place every ten years since 1790.

The individual digital records from the 1950 census became available to the public for the first time on April 1, 2022.

Overcast-Hawks, a sophomore, and the other 17 students in Professor of Sociology Ana-Maria Gonzalez Wahl’s “Sociology of Work, Conflict and Change” class, used the demographic snapshots of people in their own family trees to better understand bigger picture societal trends.

Using the 1950 census data, students found details on grandparents or great grandparents with jobs as textile workers, schoolteachers, assembly line workers, business owners, labor union organizers and college professors. The students also had conversations with their families and delved into earlier census records and other genealogical records to trace work histories going back three generations.

This was a project to discover not just the jobs that family members had done, but how those tied to broader societal forces, including post-war prosperity, the GI Bill, the housing boom, the labor movement and workplace discrimination.

“The individual biographies become a window for understanding the broader terrain of the American economy,” Wahl said. And, the 1950 data added to that understanding.

“I believe that there are so many great resources out there, but we live in an age of information overload,” Wahl said. “Yes, all this data is available, but how do we find what we’re looking for and then tell a story that’s meaningful based on that data.”

For sophomore Mia Handler, exploring the 1950 census records yielded draft registration cards for three of her great grandparents. She also found her grandmother’s immigration records, which documented her arrival to this country with her mother and sister from Hungary.

Because census takers also recorded state or country of birth, she could also get a glimpse of the demographic makeup of the neighborhood in New York City and see that many of those living on the same block were also born in Eastern Europe.

“When it became really difficult to find records for my family using the census records before 1950, I realized my family history, at least in America, didn’t go that far back,” said Handler, who is majoring in sociology.

“We used what the students found to look at the way place shapes the landscape of educational and economic opportunities,” Wahl said.

Senior Rory Britt presents his family work history to his classmates.

In 1940 census records, one of senior Rory Britt’s great grandfathers was listed as a truck driver, with a salary of $1,200. His great grandmother was listed as a homemaker. His grandfather, who was one year old at the time, was listed as “baby.”

“Out of the 20 or so records on that page, I think there were about 18 homemakers, six truck drivers, an accountant and a dentist,” said Britt, who is double majoring in politics and communication.

By 1950, his grandfather was 11 and the census taker noted his occupation was “student and news boy.” His great grandfather’s occupation had changed to train sales with a large jump in earnings.

“In a 10-year time span, I could see the post-war boom and upward mobility happening,” he said.

Exploring family history in this way also sparked conversations among classmates that went beyond documenting work histories.

“The class gave us a lot more perspective on why certain problems might exist in the workforce, the work that has been done to try and rectify those, and the work that can still be done that can be guided by the history that we've learned.” Senior Rory Britt

“When we talk about the world of work we, I think, have some pretty common conceptions of the issues that exist – things relating to employment discrimination or the different breakdowns of races or genders in certain careers or the histories that have informed where people live or why they work in certain industries,” Britt said. “What makes sociology so interesting is you take these subjects and rather than just accepting them, you really begin to ask why.”

Wahl, whose research focuses on social stratification, labor relations, housing, and the politics of inequality, has years of experience exploring census data. She provided guides for navigating census records and other reference sources.

“I hope they have discovered that their own history reveals the resilience of individuals across time,” Wahl said. “That is the common ground in navigating a world in which your job becomes such a key determinant of your opportunities.”

Categories: Experiential Learning, Research & Discovery

Wake Forest News

336.758.5237

media@wfu.edu

Meet the News Team

Headlines

Wake Forest in the News

Wake Forest regularly appears in media outlets around the world.