Albatross in WFU Study Circles the Globe in 90 Days

A Laysan albatross tracked by Wake Forest University biologists has flown more than 24,843 miles in flights across the North Pacific to find food for its chick in just 90 days — flights equivalent to circling the globe.

A Laysan albatross tracked by Wake Forest University biologists has flown more than 24,843 miles in flights across the North Pacific to find food for its chick in just 90 days — flights equivalent to circling the globe.

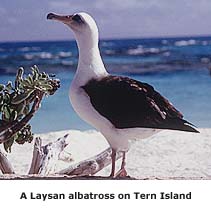

“That’s quite a long way for take-out, isn’t it?” quipped David Anderson, the biologist who has been tracking the flights of the Laysan and black-footed albatrosses by satellite since January. The seabirds nest on Tern Island in Hawaii, an atoll that is part of the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

“Before this study, we would have never thought a bird would fly as far north as the Aleutian Islands from Tern — and not once but four times,” he said. “And he’s not alone. We’ve had other birds make long and repeated trips east to the San Francisco Bay and back and to other locations on the West Coast — almost to the same spot.

“Probably the most surprising thing that we’ve found is that the birds that nest out in the middle of the ocean are traveling all the way back to continents to find their food,” Anderson said. “At this point, it’s a mystery why a bird nests that far away from a continent but goes there to feed. Audio Button

Since the Laysan’s feat, three other albatrosses have logged globe-circling mileage in feeding trips for their chicks, including a female black-footed albatross that logged the miles in just 79 days.

Thousands of school children in the United States are following the birds along with Anderson and his research team through The Albatross Project’s e-mail bulletin board and Web site.

Supported by a $200,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, the study seeks to find ways to reduce worldwide albatross declines of up to 10 percent a year and answer evolutionary questions raised by the seabirds’ long sojourns at sea.

So far, Anderson has tracked 29 of the birds through the use of small radio transmitters taped between their wings. Orbiting Argos System satellites pick up the signals and relay them to a processing station in France before the coordinates are sent by e-mail to Wake Forest in Winston-Salem, N.C., where Anderson and Patty Fernandez, a graduate student in biology, distributes the information by e-mail to participating classrooms.

As is the case with other species of albatross, researchers found the birds make short trips from Tern for food until their chicks are about a month old when they begin making long trips that take them away from the island for weeks at a time.

Anderson has also found differences in where the two species prefer to find their meals of squid and other food that their stomachs separate into the oily meals they feed to their chicks back on land. “Laysans fly north, northeast and northwest while black-footed albatrosses fly east and northeast,” he said.

Albatrosses have long been part of maritime lore because of their huge wingspans and ability to glide effortlessly over the surface of the ocean. In the early 17th century, mariners believed drowned sailors were reincarnated in albatrosses and feared that killing them would bring bad luck — the theme of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.”

Anderson hopes his research will have the opposite effect. “Ultimately, our goal is to identify where the birds feed,” he said. “Once we know that, we can look at some of the factors that previous work has indicated may be causing the declines — such as accidental bycatch by longline fishing fleets — and see if that is, in fact, a problem we need to address in the North Pacific.”

The Wake Forest University study is not the first satellite tracking of albatrosses. French, Australian and British researchers have tracked wandering albatrosses and other large species in Antarctica and the Southern Hemisphere, where most species of albatross are found, since the transmitters became available about five years ago.

But the Albatross Project is the most extensive tracking in the Northern Hemisphere, the first in the North Pacific, and the first to involve schools in the tracking through e-mail and the Internet.

“Every morning when we come in, they all want to know, ‘Where is my bird?'” said Janneke Bogyo, technology teacher at the Tuscarora Indian School in Tuscarora, N.Y. “The project is helping them learn a lot about maps, ecology, latitude and longitude as well as the scientific method.”

Anderson said that biologists on Tern have already begun to collect the radios of returning birds as the study’s first tracking season nears its end. Tracking will resume again on Tern in November when another nesting season begins.

Participation in the project is free and open to anyone with e-mail and Internet access, Anderson added. To sign up, go to the “Join the Project” section of the Albatross Project Web site or type “subscribe albatross” in the body of an e-mail message to listserv@wfu.edu.