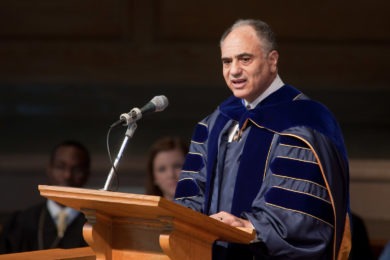

Weathering Wake: The African-American Experience

Founders’ Day Convocation Address

Feb. 26, 2009

Wait Chapel, Wake Forest University

Parent’s speech:

Thank you, Jermyn, for the introduction. Greetings to President Hatch, Provost Tiefenthaler, Dean Fetrow, my colleagues, students, alumni and friends of the University.

Thank you, Provost Tiefenthaler for the invitation to speak. I also thank Dean Herman Eure and Mr. Doug Bland for generously giving me their histories of race relations and documents that they’ve collected. JaNee Jones, my student assistant, provided valuable support. Mrs. Jing Wei and media relations in the Athletic Department provided technical support for the audio portion of this presentation. I’d like to acknowledge the articles that I’ve drawn on in the Wake Forest Magazine and the Old Gold and Black, especially the series on race relations by Alex Reyes and Jessica Pritchard. Finally, thank you Dr. Lynne Reeder, president of the Association of Wake Forest University Black Alumni (AWFUBA), for organizing interviews, and the alumni who shared their experiences with me.

I dedicate these remarks to my son Fred, class of ’09.

Two of our former colleagues have defined the African-American experience. Emeriti professor Dr. Dolly McPherson, Angelou’s Boswell, explained that the African-American experience is both celebratory and transcendent, “a source of regenerative strength.” Former Divinity School professor, Dr. Bradley Braxton, now pastor at Riverside Baptist Church, wrote that the African-American experience “is the communal quest … for legitimate self-affirmation…, which gives rise to and nourishes itself.” This regenerative quest is woven into the fabric of Wake Forest University.

Anthony Parent

It would take, as my mother might say, a month of Sundays to give a proper history of African Americans at Wake. Nevertheless, I hope that my talk will capture the ethos of the African-American experience.

Desegregation, which Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson has called “one of the most important events in the history of Wake Forest,” happened when most Southern white colleges were in lockstep against it. The Feb. 1, 1960, sit-in movement in Greensboro crystallized the moral and ethical issues of segregation at the college. Wake entered the movement on Feb. 23, 1960, when ten of her students joined twelve Winston-Salem State Teachers College students in a sit-in at the downtown F.W. Woolworth lunch counter. The sit-ins, “extensively” covered by the Old Gold and Black, linked the lunch counter struggle to the admission of black students to the college.

Students affiliated with the Baptist Student Union and under the tutelage of M. Macleod Bryant formed the African Student Project to find a black candidate for admission. They solicited an application from Edward Reynolds, a Ghanaian student, and paid for him to come to North Carolina in the fall of 1961. His application, however, was never submitted because the trustees had not yet changed the admissions policy. With President Tribble’s help and the African Student Project’s financial support, Reynolds entered Shaw University. Even Reynolds later asked rhetorically: “Isn’t it strange that Wake Forest students who wanted to integrate had to go across the Atlantic to find a black student?”

The following spring the trustees reversed their position. On April 27, 1962, the Board of Trustees voted 17 – 9 to end the university policy of racial discrimination. The Old Gold and Black cheered the sea change as a triumph in the struggle for civil and human rights. “No longer will we be compelled to live under the shadow of segregation. No longer will Wake Forest students participating in sit-ins be met with cries of ‘clean up your own backyard first.’ No longer must we admit to being a Christian college which does not accept fully the principles upon which it was founded.”

Reynolds matriculated during the summer session 1962. He felt that it was an unforeseen blessing that his admission had been delayed. During his time at Shaw he identified with the black community, an identification that would later assist him at Wake. “When I was here, I was very happy at Wake Forest, and I was very much accepted,” he reminisced, “but in a way, deep down, I needed to identify with something.” That something was the African-American experience.

Although most of his encounters were pleasant, he did recall two racist incidents. The first, receiving a picture of a gorilla in the mail, something that he called not worth mentioning, was evidently a painful memory. The second, he felt, was worth mentioning.

Although he had received “A’s” on all of his examinations, his professor gave him a “B” in the course. When he asked why, the professor responded “that a B was a good [grade] for a Negro.”

Unlike Reynolds who lived in the dorms, the first black women students were day students. Patricia Smith, was the first African-American woman graduate in 1966. She later distinguished herself as a data systems supervisor with AT & T before her untimely death. Sylvia Rosseau, a 1968 graduate, later a Superintendent of Los Angeles Unified School District, recalls her Wake experience as “positive.” A married, transfer student from the University of Cincinnati, she found the small college atmosphere “hospitable,” and the English department a “very welcoming place.”

During the mid-sixties, the college began recruiting black men as athletes. Ross Griffin credits both Edward Reynolds and Brian Piccolo with assisting in this effort. Piccolo’s “increasing…sensitivity to racial issues,” because of his friendship with Gayle Sayers, led him to help fellow alumni John Mackovic recruit the first African-American football players at Wake Forest. They brought a number of these recruits to meet Reynolds who encouraged them to come to the college. Robert Grant, Kenneth Henry, and Willie Smith enrolled in the fall of 1964, making Wake Forest the first college in the ACC to integrate its football program. Although Smith left after his freshman year, Bill Overton transferred to Wake as a junior in 1966. Grant, Henry, and Overton were drafted into the NFL.

Wake also pioneered two areas in athletics traditionally closed to blacks in the 1960s. Freddie Summers became the first black quarterback at a historically white southern college in 1967, setting records in passing and scoring. Audley Bell, a Jamaican, became the first black tennis player in the ACC in fall 1969. The Old Town Country Club closed its doors on the tennis team rather than admit Bell on the court.

The athletic highlight of this era was Wake Forest defeating UNC to win the ACC championship in 1970. Larry Hopkins (MD ’77) emerged as the star of that game spearheading a drive to score a touchdown during the last three minutes of play. (Hopkins was the first of several outstanding African-American running backs that included leading rushers James McDougal (’80) and Chris Barclay (’06).) Of course, Dr. Hopkins, an obstetrician on the faculty of the Wake Forest Medical School, remembers this triumphal moment.

Unfortunately, like Reynolds, he encountered professors who believed that blacks, especially athletes, didn’t deserve “A’s” despite their test performance. Although he was in Gamma Sigma Epsilon, the national honor society for chemistry, his professor would only give him a “B” in chemistry, reasoning he must have cheated because a black football player was incapable of earning an “A”. He received the same treatment from a physics professor. When Hopkins went to that professor’s house on Faculty Road to discuss the grade, he was directed to the back door by his wife.

Billy Packer (’62), now a noted television announcer, played a similar role in recruiting basketball players that Piccolo had played in football. In the winter of 1959, Packer, a Demon Deacon guard, traveled across town to see Cleo Hill play at Winston-Salem Teachers College. The experience led Packer and Hill to organize scrimmages between the two squads at each others’ gym without the permission of their respective coaches, Horace “Bones” McKinney and Clarence “Big House” Gaines. These integrated contests were illegal in Jim Crow south, operating outside of the purview of the press and the police.

When Packer became an assistant coach in 1965, he reinstituted the scrimmages and began to follow the path blazed by Gaines and other CIAA coaches, recruiting cagers from the Harlem playgrounds. Wake recruited Norwood Todmann who enrolled in the fall of 1966, the first African-American in the ACC (along with Charlie Scott of UNC). Todmann later “persuaded” his friend Charlie Davis to follow him in 1967. Davis, who once scored 52 points in a game, was extraordinary, garnering All ACC honors three years in a row, All ACC Player of the Year in 1971, and an NBA contract.

Gilbert McGregor (1971), a teammate of Davis and Todmann, and now a television commentator, remembers the harassment of African-American athletes. He remembers that in 1968, when black students numbered twenty, security guards followed both the black athletes and the white women “suspected of dating” them. Student Health Services sent postcards to black athletes, to come in to be checked for STDs, but sent none to white athletes. “Some of us were tested, some weren’t, and some simply refused,” he recalled. “The university wasn’t prepared — they didn’t think it through. Eventually some black females were brought in.”

Broadening recruitment to non-athletes in the 1970s, especially African-American women as residential students, ushered in a new era at Wake Forest. The first black female residence students Deborah Janet Graves (’73) and Muriel (Beth) Elizabeth Norbrey (’73) matriculated in the fall of 1969. The addition of black women caused at least one white parent to object to his daughter living with a black roommate.

Dr. Scales’s response demonstrates the college’s commitment to inclusive housing. Scales wrote that “we have never submitted to our fears…As we do not seek congeniality by race, neither do we demand that suitemates have the same religion, the same vocational interest, or the same tastes in art or athletics or music. A university’s residence policy should invite diversity and thereby broaden the experience of our students.”

The addition of African-American women as residential students provided the seedbed for community development. African-American students engaged themselves in extracurricular campus activities. Mutter Evans (’75) recalls that blacks, although a minority, were woven into “fabric” of the college. Evans, who at 26 became the youngest African-American to own a radio station, WAAA, remembers how active blacks were on Pub Row, publishing poems and essays.

Blacks rushed the societies and pledged the fraternities (Alpha Sigma Phi pledged two black students in 1966-’67). Blacks were also active in Student Government and student life. For example, Beth Norbry joined Sophs Society, served as secretary in the Student Government Association and was nominated homecoming queen by Poteat House and won, a testament to her service. (Norbry is now Mrs. Beth Hopkins, attorney and adjunct professor in the American Ethnic Studies Program and the history department.)

The Afro-American Society, a self-help group for all black students on campus, was founded by Howard Stanback and Freeman Mark in 1969. The society advocated for black studies and black faculty, and was active in celebrating African-American culture. It emerged as a presence on campus in the winter of 1970. Tensions between African-Americans and the university flared up on Feb. 1 when two black students were accused of cheating on a take-home history examination. The chairman of the Honor Council rushed to judgment, telling members of the Afro-American Society that the students were guilty before investigating the incident. One student was exonerated, the other summarily expelled. Protesting the handling of the case — hearings held in the wee hours of the morning, a warrant served by deputy sheriffs in the Afro-American Society lounge — the black students refused to stand during the National Anthem at the basketball game. They also contemplated leaving the University in mass, transferring to Temple University.

Spiritual strivings led to the creation of a choir and bible study associations. Ollis (Zonnie) Muzon Jr. (’75) began the Afram Choir in the winter of 1974, partly because of his conflicted feelings about not pursuing the ministry. (He is now an army captain and chaplain just home from Iraq.) James Harrison was the first pianist. They were simply bringing their sacred songs to their college community. The Afram Choir was eventually institutionalized as the Gospel Choir.

“The sense of place provided by the Gospel Choir cannot be underestimated,” writes Rev. Marcus Ingram (’99, DIV ’06). Although the choir is not exclusively African-American, for a generation it has been “the largest student-organized gathering of African-American students.” “Experiencing the choir enhanced the Wake Forest experience,” adds Ingham, and “helped provide the needed encouragement to persist to graduation.”

The absence of an African-American chaplain to meet their spiritual needs led to the founding of the Black Christian Fellowship and Forest Fire Christian Fellowship. Yet unlike the Gospel Choir, African-American Christian fellowships never received formal affiliation. Lacking an institutional home has been disconcerting. Ingram said in 2004 that “African-American students [assume] that all of Campus Ministry is going to be white, which creates a level of discomfort.”

The Afro-American Society advocated for black faculty. The college slowly responded. The School of Business and Accountancy hired the first African-American — Joe Norman, a CPA — to teach in the spring 1969. Dr. Herman Eure (Biology) and Dr. Dolly McPherson (English) were the first tenure-track professors. Both hired in 1974 had had previous history with the university. Eure (Ph.D. ’74) was the first black graduate student. McPherson had accompanied Angelou to her first talk. They were joined by Laura Rouzan (Communications) and Sandra Daniel (French, Romance Languages); both left after a short stint.

Willie Pearson Jr. (Sociology) and Maxine Clark (Psychology) were hired in 1980, after President James R. Scales mandated every faculty search include a black candidate. The University reached a “milestone” in 1982, hiring Dr. Maya Angelou as lifelong Reynolds Professor of American Studies. This first era of faculty recruitment ended in 1984 with the appointment of Dr. Eddie Easley to the School of Business and Accountancy.

Dr. Angelou is our most distinguished and highly celebrated professor. Her appointment became a beacon to African-Americans nationwide. Clearly Wake Forest was committed to African-American culture. (Indeed, Dr. Angelou’s appointment figured prominently in my decision to come to Wake Forest.).

The generation of students from 1974 to 1985 was still a small knot, approximately a dozen female and a dozen male non-athletes. They remember the safe havens created by Bryant, Angelou, Ruzon, Eure, and Dr. Charlie Richman (Psychology). Dr. Dolly McPherson, on the other hand, was remembered for being tough. Students fondly recalled the black housekeeping and cafeteria workers including Rosetta Johnson and Ms. Flossie. (I have yet to find out Ms. Flossie’s surname; the alumni reminded me that service workers wore name tags bearing their first names then.) These women were highly respected in their churches and community, even if they were often anonymous to most campus residents. Mrs. Zella Johnson, administrative assistant in the biology department, also evoked positive memories. The alumni remembered Bill Starling, director of admissions, as “incredibly inclusive.”

Black alumni recall a dramatic shift in female recruitment from five resident students in 1979 to twelve in 1980. The class of 1980, labeled “too assimilated” by the Old Gold and Black, ironically, led the demonstration against the Confederate Flag in the spring of 1979. The African-American students took offense to the Kappa Alpha’s Old South Week tradition of flying the Confederate Flag and wearing their Confederate uniforms to class. (This class also remembers the Kappa Sigma’s tradition of blackening their faces like minstrels and performing as the “Five Screaming Niggers.” They also hung a black effigy outside of their house for a week before burning it.) The students’ sensitivity was heightened because Old South Week dovetailed with Afro-American Information week, which brought community organizations like the NAACP and the Urban League onto campus.

Marylyn Little and Jocelyn Burton went downtown and purchased a Confederate Flag. Burton and Jimmy Steele, foreshadowing his later media relations position at the Wake Forest Medical Center, alerted the local media. The students marched around the Quad and then burned the flag on the steps of Reynolda Hall. Chaplain Ed Chrisman (’50, JD ’53) later told Burton that the Kappa Alphas were hurt by the burning of the flag.

This led Burton, who became president of the Afro-American Society, to meet with the KAs. They worked out a compromise. The KAs would no longer wear their uniforms to class during Old South week, or come to the dorms singing Dixie. They would place their logo on the flag, identifying it with their organization and not the cause of continuing race segregation. This reconciliation was so successful that the KAs and the Society would later co-hosts events.

Alumni felt that the African-American students from the seventies through the nineties didn’t “sort” out by class; rather they were a community, not knowing or caring what each others’ parents did. This community experience helped them succeed through a difficult, at times even hostile, experience at Wake. Reconciling this tension tempered their success at the college and in later life. They reckoned that successful African-American students were self-starters who weathered the experience. Disillusioned students, on the other hand, were “worn” down by their experience.

The example of Greg Jones, who had transferred to Wake Forest from Appalachian State, demonstrates that this was not an either/or situation. Jones’s advisor told him that the only reason that blacks were at the College was because of a federal grant. This harassment demoralized him so much that he walked over to the Reynolds plant where his father worked to tell him that he was dropping out. When he arrived at the gate, he met one of his father’s co-workers who told him how proud his father was that he was at Wake Forest. Rather than disappoint his father, Jones turned around and walked back to campus. He did not drop out and earned his degree in 1977.

Black alumni remembered advising by white professors as a mixed bag from 1975 to 1985. Jocelyn Burton credits Lu Leake, Dean of Women, as instrumental in her going to graduate school. She is now Chief Attorney, Superior Court of California, County of Santa Clara. On the other hand, Deborah Rascoe (’85) recalls being told that she would never become a dentist by one professor and encouraged to follow her dream by another. She did become a dentist.

Perhaps the most disturbing story I heard was that of Angela Patterson (’85). Patterson remembers that “my white professor told me that black people didn’t know how to write,” yet she became the Senior Orator, giving a speech “White, Unlike Me”. She also became president of the College Union … and contributed to the plans to build the Benson Center. She feels that “the lack of encouragement I received at Wake [and] being told medical school was certainly not an option,” were “secondary” to her feelings of racial oppression. “I overcame all of those obstacles.” “I did not let the racism deter me. I barely graduated with a major in biology and I managed to get into [Howard] medical school two years later and graduate. I am …Angela Patterson-Jones, M.D., Double Board Certified in Neonatology and General Pediatrics.”

Chris Leake (’85) “hated” his experience at Wake Forest. His father had pastored a generation of African-American students at Philip’s Chapel. Leake felt that the college was very segregated; African-American students often sat together in the cafeteria. Like Patterson, Leake deplored the consul of his faculty advisor. He recalls at graduation telling her that she had been a “real mother” to him, pausing just long enough that she might understand his phrasing. She did not.

Barbie Oakes (’80), presently the director of Multicultural Affairs Office, said that this generation of black students fit the profile of what William G. Bowen and Derek Curtis Bok identified in their book, “The Shape of the River.” “African-American students were successful despite the lack of institutional support.”

Wake’s effort at institutional support resulted in the Office of Minority Affairs. B. Lynne Reeder (’79), Ph.D., Director of Counseling Center and University Testing Services at UNC Wilmington, remembers that the idea for a minority affairs office grew out of a research project she and Elizabeth Legena Blue (’78) wrote for Professor Laura Rouzan.

After making their findings known to the administration, the college responded in 1978, when minority admissions were on the decline, creating an Office of Minority Affairs and hiring Dr. Larry Palmer. Reporting directly to Provost Wilson, Palmer directed the Minority Affairs Office from 1978 to 1981. Dr. Eure succeeded Palmer, directing the office for three years, while continuing to teach biology. Suzette Jordan (’81) served as temporary director for two years. Students found her both “accessible and supportive.” Alumni from this era remember that Minority Affairs sponsored Prospective Students and Future Freshman Weekends. Potential recruits spent the weekend with current African-American students. Feeling part of the community influenced their decision to come to Wake Forest.

President Hearn moved the Minority Affairs Office to Student Life in 1986, again hiring a permanent director. Vice President Ken Zick appointed Dr. Ernie Wade Director of Minority Affairs and a year later (appointed) Harold Holmes, Dean of Students, the first African-American dean. Wade coordinated recruitment in the admissions office and hired Gloria Cooper to go find the students.

The University developed two important scholarship funds: the Joe Gordon Scholarship, named after the first African American radiologist at Baptist Hospital, and the Black American Scholarship. Wade’s leadership and Cooper’s energy boosted African-American recruitment, more than doubling the percentage of black enrollment from 3.5 in 1986 to 7.7 in 1995.

The new number of students led to the strengthening of historically black intuitions on campus. The four major national black fraternities, Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Inc., Omega Psi Phi, Kappa Alpha Psi and Phi Beta Sigma, a presence in the seventies, blossomed in the nineties. When the University opened up to sororities, Alpha Kappa Alpha and Delta Sigma Theta took root.

“The prominence of Greek Life at Wake Forest,” reasoned Marcus Ingram, an Alpha, “made this a natural and necessary addition to the slate of student activities, for [black] students [were] either not interested in or welcomed by predominately White Greek organizations.” “The positive expression of Blackness in a predominately White environment becomes essential.”

Tiffany Callaway, president of the campus chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Inc. in 2004, echoed his sentiment “For me, especially being at a school where the majority is white, it’s even more important to have organizations for minorities because we support each other.” African-American women also started the Nia House, culturally inspired theme house.

Katina Parker, a sister of Nia House, said that her class felt that they were “constantly being challenged,” especially the males. She especially remembers a Gym Jam in the Pit in 1995 being pepper-sprayed. The students questioned why their alcohol-free parties were heavily policed by campus security, but white parties serving alcohol were not. She also recalls the Critic, a reactionary student paper, attacking Dr. Angelou and other black and woman faculty.

Perhaps singular achievement of the Black Student Union (previously the Afro-American Society) was its campaign beginning in 1991 to elect an African-American Homecoming Queen and King. Consolidating their vote around an attractive candidate that would have cross-campus appeal allowed them to elect 13 straight homecoming queens and kings. Their success caused a vicious attack in 2003 when the Howler yearbook questioned: “Should Wake Forest continue its 12-year tradition of electing a Homecoming King and Queen that represents only a small portion of students, or will we change our ways and elect the male and female that best represent our school?” A vehement protest by the African-American community resulted in the editing out the repugnant statement. That fall’s homecoming vote resulted in a tie for queen, with a white and black woman sharing the crown.

President Hearn also authorized a Committee on Race Relations, chaired by Provost Wilson in 1988. The committee report recognized the need to increase underrepresented minorities on the faculty, especially African-Americans. On the Reynolda campus in 1987-88 there were only six blacks in a faculty of 263 or 2.3%. The first wave was a direct result of an affirmative effort to double the number of African-American faculty to twelve by 1990. The goal was successful, hiring six tenure-track professors in the college: Alton Pollard (Religion), Beverley Wright (Sociology), Debra Buggs Boyd (Romance Languages), Barbee M. Oakes (Health and Exercise Sciences), Anthony Parent (History) and Lorraine Stewart (Education). Susan Brown Wallace (Psychology), and Yomi Durotoye (Politics) joined the faculty as visiting professors. Luellen Curry joined the law faculty in 1989.

A second wave of faculty hires began in 1993 to 1998. At the professional schools, Simone Rose and Tim Davis joined Curry in the law school and Derrick Boone joined the Babcock School of Management. The College hired five African-American and two African faculty members: Erik Watts (Communication), Nina Lucas (Theater and Dance), Richard Heard (Music), Debra Jessup (Calloway School of Business and Accountancy), Cheryl Leggone and Earl Smith (Sociology), Simeon Islesanmi (Religion), and Sylvain Boko (Economics).

During this phase, blacks attained academic leadership positions for the first time. Smith’s appointment included Director and Rubin Chair of American Ethnic Studies. Smith and Eure became the first and only African-American department chairs. Islesanmi became director of Graduate Studies in Religion, Lucas, director of the Dance Program; Boko developed and directed the Benin Summer Study Program, and Leggone became director of Women’s and Gender Studies Program. Oakes left the college faculty in 1995 to become the director of Multicultural Affairs.

During this era of expansion WFU once again made athletic history when in 1993 and 1997 athletic director Ron Wellman named African-Americans head coaches of football and women’s basketball. Jim Caldwell became the first African-American in the ACC. Caldwell remembers this as a “bold step” on the part of Wellman, whom he called a “maverick” and Hearn, whom he called “outstanding.” The College Football Association in 1995 recognized the Wake Forest football team for the highest graduation rate in the country. Caldwell led the fundraising drive to build Bridger Field House. His chief athletic accomplishment was to lead the Demon Deacons to the Aloha Bowl in 1999.

Coach Caldwell, now head coach of Indianapolis Colts, sent more than 33 of his players to the NFL, including Fred Robbins, Desmond Clark, Calvin Pace, and Ovie Mugheli. Eight members of Caldwell’s staff are either coaches or are in the front office in the NFL, including Diron Reynolds (’94, MALS ’99), defensive line coach for the Colts.

Charlene Curtis was head coach of the women’s basketball team for seven seasons from 1997-2004. She rebuilt the program and generated spectator interest in women’s basketball. Her players did well, both in the ACC and in the classroom. All of her scholarship players graduated.

The most memorable athletic moment during the ’90s was the Demon Deacons winning the ACC basketball championship in March 1995. Randolph Childress (’95) belonged to a cast of Wake Forest stars and NBA draftees that included Frank Johnson (’81), Tyrone “Muggsy” Bogues (’87), Rodney Rogers (’93), Tim Duncan (’97), Josh Howard (’03), and Chris Paul.

Black enrollment peaked in 1997 at 9.2 percent, but then took a precipitous downturn in 1999. Reacting to the 1994 U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruling that the University of Maryland’s Banneker scholarships, awarded exclusively to African-Americans, was unconstitutional, the college had changed its scholarship program. The Gordon fund was opened to “underrepresented” students and the Black Scholarship fund was discontinued.

The loss of the Black Scholarship and reduced access to the Gordon Scholarship hurt black recruitment. The percentage of African-American students in 2003 declined to its low point of 5.9%, reaching back to its 1989 level. Increases in the black freshmen classes in 2005 and 2006 have raised the percentage of African-Americans in the college to 7.1 and 6.6 respectively.

African-American faculty attrition dovetailed with the decline in black enrollment. What’s most disturbing is the loss of the third wave of faculty hired from 1999 to 2002. Their number includes Eve Shockley and Michael Hill (English), Valerie Cooper (Religion), James Wilson (History), Bradley Braxton (Divinity), and Nat Irvine (Babcock School of Management). Every one of these professors has left the university. A 100 percent attrition rate should give us pause. During the ten-year period from 1997 to 2006, Pollard, Buggs-Boyd, Stewart, Jessup, Watts, Pearson, and Leggon left the University. In all, 15 African-American professors left the university during this decade, when only two retired. To date, only McPherson (2002) and Easley (2005) reached emeriti status.

The Reynolda Campus has been refreshed by a fourth wave, a new generation of African-American appointments. Beginning in 2003, nine new faculty members have received appointments, including Roy Carter in the art department and LeRhonda S. Manigault in religion. If the faculty attrition rate should give us pause, the example of both the law school and the English department deserve our praise, both for retention and recruitment. Rian Bowie, Erica Still, Melissa Jenkins, Judith Irwin-Mulcahy, all now teach in English. The Law School has added Tracey Banks Coan, Kami Simmons, and Omari Simmons to the ranks of Curry, Rose and Davis. Significantly, Blake Moran became the dean of the law school, becoming our first African-American academic dean. Eure also became associate dean, Wanda Brown, associate director of the Z. Smith Reynolds Library, and Harold Holmes, associate vice president, the first African-American to reach that position.

Omari Simmons (’96) deserves special mention, for he is the first African-American undergraduate alumnus to become a faculty member. African-American alumni from Simmons’s generation appreciate the education that they received at Wake Forest and the mentorship of African-American faculty. Dr. Melissa Harris-Lacewell (’94) writes that “I have come to appreciate Wake more and more over the years. You were a critical part of that core faculty who went out of your way to make it possible for us to survive and thrive on an often hostile campus. Now that I am a faculty member I understand much more intimately the sacrifices it required to care for us so diligently.”

Dr. Marc E. Dalton (’92, MD ’97): writes “I often talk with alumni and we comment on how WFU prepared us well for our careers after we left. We also wonder if Wake is aware of the success of its African-American alumni. It is amazing what we have accomplished. We learned so much there, most of which was outside of the classroom. Mentorship from the faculty such as you, Drs. Eure, McPherson, Angelou, and others, allowed us to be successful. I am proud of the education I received there and of the lifelong friendship I made.”

The university has identified at least 2,196 African-American alumni. With the help of the Association of WFU Black Alumni, I have selected a bakers’ dozen, an Honor Roll of alumni who have excelled in their respective fields:

Arts: Mr. Jeffrey Wendell Dobbs (’77), Dance

Athletics: Mr. Timothy T. Duncan (’97), San Antonio Spurs, Pro Basketball Player

Banking: Mr. Simpson O. ‘Skip’ Brown Jr. (’77, MBA ’86), TriStone Community Bank

Business: Mrs. Sheereen Miller-Russell (’00), MTV Networks, Account Executive

Education: Sylvia Rousseau (’68), Superintendent, Los Angeles Unified School District

Entertainment: Mr. James Lamont DuBose (’90), Television Producer

Labor: Mr. Clark D. Gaines (’78), Assistant Executive Director, NFL Players Association

Law: Hon. Alfred Sherwood Irving Jr. (’81), Superior Court of the District of Columbia, Magistrate Judge

Medicine: George H. Perkins, M.D. (’85), Associate Professor of Radiation Oncology, University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center

Media: Mr. Gilbert Ray McGregor (’71), the Charlotte Hornets, Broadcast Analyst

Military: Col. Cyrus Edward Gwyn Jr. (’81), USAF Defense Information Systems Agency, Colonel (DISA Continental U. S. Commander)

Politics: Ms. Donna Fern Edwards (’80), U.S. Congress, Congresswoman

Public Intellectual: Dr. Melissa Harris-Lacewell (’94), Princeton University, Associate Professor of Politics and African-American Studies, author, and commentator, MSNBC

Religion: Rev. Dr. Archie Doyster Logan Jr. (’72), Apex School of Theology, the Executive Vice President and Dean of Distance Education

We are all enriched by the contributions of African-Americans to Wake Forest University and African-American students, alumni, faculty, and staff are proud of their association with the University. I believe that I can speak for all in saying, we are Demon Deacons; we are Wake Forest University.

Thank you.

Categories: Happening at Wake, Research & Discovery

Wake Forest News

336.758.5237

media@wfu.edu

Meet the News Team

Headlines

Wake Forest, Palmer Foundation announce partnership to promote leadership and character through golf

Wake Forest in the News

Wake Forest regularly appears in media outlets around the world.