Son seeks father, finds literary and artistic avant-garde

Words Awake!, the three-day symposium showcasing Wake Forest’s literary legacy, launched with a spectacular start Friday evening when Tom Hayes (’79) premiered his documentary film, “Editor Uncut,” about his father, Harold Hayes (’48), who as editor of Esquire (1963-1973) marshaled the talent that established the magazine as the disquieting mirror of its age.

“It is fitting that the film should be shown at Wake Forest University first,” said Tom Hayes, “because my father had such a close connection to college. He attributed almost everything he became to Wake Forest.”

In his introduction, Tom Hayes recounted his film’s inception. In 2007, he read a long article about his father in Vanity Fair entitled “The Esquire Decade,” by Frank DiGiacomo. Drawing from the Harold Hayes Papers (“a treasure trove “) in Special Collections at Z. Smith Reynolds Library, DiGiacomo detailed the elder Hayes’ life: his birth in Elkin, North Carolina, his youth in Winston Salem, his formative college years at Wake Forest, his rise in Esquire, his subsequent role as an wildlife conservationist and author of three books on Africa.

“I wondered,” said Tom, “why did [DiGiacomo] give that much space to someone who had been gone for almost twenty years?

“As a kid growing up I’d see these magazines appear on the coffee table. ‘Look what I did,’ my dad would say. But I didn’t really understand what he did. I realized that I had a last chance to find out about his life from his colleagues. I have spent the last three years chasing down people who knew my father. Now I understand a lot better.”

In the ’60s, Harold Hayes cultivated writers who went on to be even greater writers: James Baldwin, William Styron, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, Gay Talese, William F. Buckley Jr., Gore Vidal, Nora Ephron, Susan Sontag and Peter Bogdonovich (who attended Friday night’s screening). Hayes also successfully enlisted establish writers like W.H. Auden, Edmund Wilson and Dorothy Parker.

“He brought together the greatest group of writers in that period – in that period that was the great period of magazine writing,” says novelist and screenwriter Nora Ephron, who worked with Hayes when she was a columnist and feature writer for Esquire in the early ’70s. “He had the exact thing that all of the great editors and producers and studio heads and politicians have, which is that he absolutely trusted his gut. He knew what he wanted. He acted on it.”

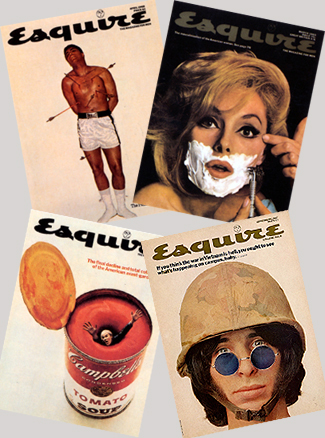

“The editorial risks he took consistently rocked the nation,” said Tom Hayes. “Like putting world heavyweight boxing champion Sonny Liston as black Santa Claus on the cover. Or Andy Warhol drowning in a can of tomato soup to signal the decline of the American avant-garde.”

“The editorial risks he took consistently rocked the nation,” said Tom Hayes. “Like putting world heavyweight boxing champion Sonny Liston as black Santa Claus on the cover. Or Andy Warhol drowning in a can of tomato soup to signal the decline of the American avant-garde.”

Long-time friend Walt Friedenberg recalled the same quality of imaginative, passion-driven determination in Harold Hayes when he knew him as a Wake Forest student in the 1940s. In Editor Uncut, Friedenberg recalled the time Harold, who played the trombone and loved jazz, heard that Dizzy Gillespie’s band would be passing near the town of Wake Forest on a southern tour.

“He went out to old 51 north and flagged down Dizzy Gillespie’s bus!” laughed Friedenberg. “Harold then invited the whole band to dinner at the college.” Afterwards, Dizzy Gillespie’s band played an impromptu jam session in the student union.

As Harold Hayes’s inspiration, charm and ingenuity were able to get Dizzy Gillespie’s band to play at a southern Baptist college in the late 1940s, the same qualities would unite at Esquire unconventional talent and unleash it in startling directions.

“Scores of careers bloomed on dad’s watch,” Tom Hayes said.

Consequently, the colleagues and friends “chased down” for interviews were a gifted lot of storytellers who have conveyed their memories of Harold Hayes with wit, verve and humor in the film. The son’s editing has kept the documentary free of heavy eulogy and has framed each interview to reveal an epoch as well as a man.

Categories: Alumni, Happening at Wake, Research & Discovery

Media Contact

Wake Forest News

media@wfu.edu

336.758.5237