One-size-fits-all weight loss doesn’t benefit all older adults

New research explores why some older adults may not see improvements in physical function, despite achieving clinically meaningful weight loss.

The National Institute on Aging has awarded Wake Forest University researchers $435,510 to study why some older adults can’t walk faster or get out of a chair easier after losing weight.

The study, “Variable Adaptive Responses to Weight Loss in Older Adults” (VARIA), will address a mystery that researchers Kristen Beavers of the health and exercise science department and Daniel Beavers of the Wake Forest School of Medicine have noted on multiple studies of weight loss in older adults at Wake Forest.

“We know obesity is a risk factor for reduced physical function,” Kristen Beavers said. “And on average, when older adults with obesity lose weight, they can typically get out of a chair a little easier and walk a little faster. But within that ‘average,’ there is always a subset of folks who don’t improve, or who even show declines in physical function.”

When the researchers looked at gait speed, for instance, they found that about 25 percent of the older adults who lost what would be considered a clinically meaningful amount of weight didn’t improve their walking speed. This was a large enough segment to compel Beavers to want to determine who they are and why one size doesn’t fit all when it comes to weight loss for older adults.

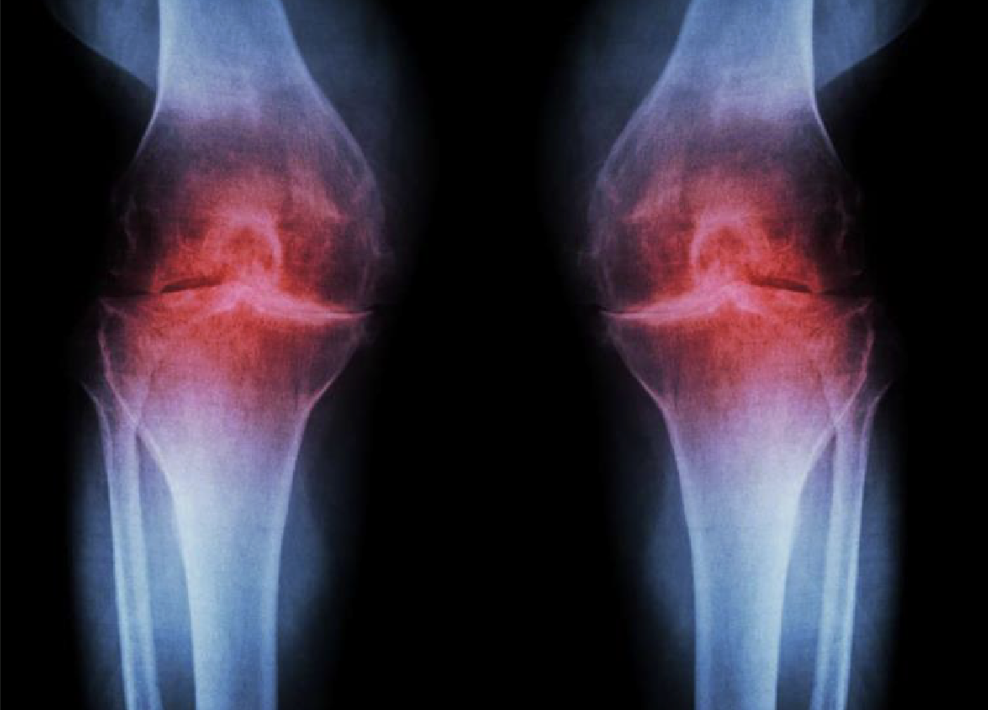

Physicians have long been careful when recommending weight loss for older adults because of the risk of losing too much muscle and bone in addition to fat. Muscle and bone loss can boost the chances of fractures. But obesity carries its own risks, increasing the likelihood of heart disease, diabetes and joint stress, for instance.

Through VARIA, the researchers would like to better understand this risk/benefit ratio by determining what predicts if an older adult will or won’t improve in physical function after a standard weight-loss program, and then design interventions to yield the highest benefit for each group.

Daniel Beavers, a biostatistician, will aggregate data from eight randomized, controlled trials of weight loss in older adults, all housed within the Wake Forest University Older Americans Independence Center, to seek potential risk factors from about 1,600 people. The goal is to pinpoint the magnitude of the variability and see what factors predict it, such as age, ethnicity or baseline functional status.

“Ideally, we would like to see everybody benefit from weight loss,” he said. “And the strength of a large dataset like this is that we can look at many participant characteristics to identify the ‘type’ of person most — and least — likely to benefit from a weight-loss intervention. VARIA will also allow us to look across the intervention strategies themselves to help us pinpoint which design characteristics are more or less likely to optimize functional response.”

This research will lay the groundwork for a future clinical trial designed to help those seniors who don’t see their physical function improve after weight loss.

“Studies coming out of Wake Forest show that, on average, weight loss yields functional benefits for older adults with obesity,” Kristen Beavers said. “We want to see if we can move the needle to help more older adults experience these benefits.”

Safe weight loss for older adults has been a focus of multiple studies at Wake Forest in recent years. Some of the results:

- New study shows more protein and fewer calories help older people lose weight safely, February 2019

- Bone loss still likely in dieting seniors, despite strength training, August 2018

- When it comes to weight loss in overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis, more is better, June 2018

- Lose fat, preserve muscle: Weight training beats cardio for older adults, October 2017

Categories: Research & Discovery

Wake Forest News

336.758.5237

media@wfu.edu

Meet the News Team

Headlines

Wake Forest, Palmer Foundation announce partnership to promote leadership and character through golf

Wake Forest in the News

Wake Forest regularly appears in media outlets around the world.